FIRE & WATER: THE GREAT DISASTERS OF SAG HARBOR

Fire and Water, a largely virtual tour, will take you through some of Sag Harbor’s most trying times. Besides the economic woes that have befallen the Village when the whaling industry collapsed, for instance, there were also disasters that changed the whole face and texture of the village, like the great New Year’s Day fire of 1925 and the infamous Hurricane of 1938. Throughout, the Sag Harbor Fire Department, formed in 1803, has kept watch and done its best to keep disasters from becoming total devastation. We are proud of their history and grateful for their courage and vigilance.

We thank Sag Harbor Fire Chief Tom Gardella and former Chief Tom Horne for sharing historical information, and Jean Held and the Sag Harbor Historical Society for their invaluable assistance in obtaining many fascinating photographs of the Fire Department and the disasters cited in this tour.

-

THE YEAR WITHOUT A SUMMER

-

THE SAG-HARBOR FIRES OF 1817 AND 1845

-

THE FIRES THAT ENDED THE DEPRESSION

-

THE GREAT WHITE HURRICANE: THE BLIZZARD OF 1888

-

THE GREAT FIRES OF 1915 AND 1925

-

THE EARLY DAYS OF THE SAG HARBOR FIRE DEPARTMENT

-

"THE LONG ISLAND EXPRESS": THE GREAT HURRICANE OF 1938

-

RECENT DISASTERS, AND THANKS TO OUR AMBULANCE CORPS AND POLICE DEPARTMENT

-

THE FIREMEN’S MUSEUM AND THE SHFD TODAY

.

THE YEAR WITHOUT A SUMMER

Fire and Water, a largely virtual tour, will take you through some of Sag Harbor’s most trying times. Besides the economic woes that have befallen the Village when the whaling industry collapsed, for instance, there were also disasters that changed the whole face and texture of the village, like the great New Year’s Day fire of 1925 and the infamous Hurricane of 1938. Throughout, the Sag Harbor Fire Department, formed in 1803, has kept watch and done its best to keep disasters from becoming total devastation. We are proud of their history and grateful for their courage and vigilance.

We thank Sag Harbor Fire Chief Tom Gardella and former Chief Tom Horne for sharing historical information, and Jean Held and the Sag Harbor Historical Society for their invaluable assistance in obtaining many fascinating photographs of the Fire Department and the disasters cited in this tour.

Tambora Today

Great September Gale in Providence, RI *

Ice Skating on the Thames *

Tambora Eruption Lithograph *

THE SAG-HARBOR FIRES OF 1817 AND 1845

In 1815, the Great September Gale occurred. Such storms were not yet called hurricanes, and its damage was mostly felt north of us, with Rhode Island taking its brunt most forcefully (see engraving). The Gale arrived on Long Island on September 23rd, at 7am, and this storm marked the first time that the unique behavior of what became known as hurricanes was described as a “moving vortex” by one John Farrar, a Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at Harvard. Historical reports for months afterwards recount rain “tasting like salt”, the grapes in the vineyards “tasting like salt”, that houses had all turned white, and that the leaves on the trees appeared “lightly frosted”. But bad as this storm was, from Fish Shape Paumanok: Nature and Man on Long Island, by Robert Cushman Murphy, we have an incredible account of the following year’s climatic devastation:

“Most appalling of all weather dates on Long Island fell in 1816, when there was frost in every one of the twelve months. This calamitous season was probably not part of a climatic trend. Rather, its phenomena have been attributed to an extraordinary screen of dust in the higher atmosphere from preceding eruptions of Soufriere [1812] and Tambora [1815], volcanoes of the West and East Indies, respectively.”

Spring arrived, but cold persisted and nothing grew well, knocked back by the repeated frosts. The Fourth of July in Sag Harbor was celebrated by citizens wearing mittens and greatcoats. All through spring and summer, there was a persistent “dry fog”. Nothing, neither wind nor rain, dispersed it, and in that permanently overcast summer the only corn that ripened to provide next year’s seed in Suffolk County grew on Strong’s Neck, because of the warming waters of Setauket Harbor and Conscience Bay. In Europe, people died and despaired, the strange lurid colors of the overcast sunsets inspired J.M.W. Turner, and it was the year Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein.

1816 was known as the "Year Without a Summer", "Poverty Year", and "Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death", and the Little Ice Age, and it wasn’t until the latter part of the 20th Century that scientists linked the eruptions of Soufriere and Tambora to this surreal weather behavior.

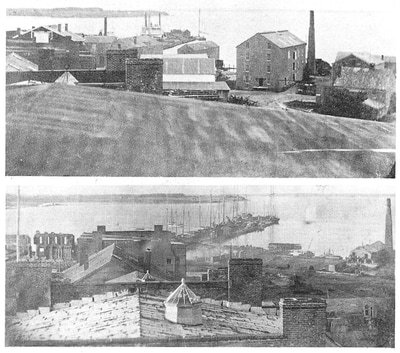

Old Sag-Harbor Lithograph *

Fire Bell from Firemen’s Museum ‡

Lithograph of Sag Harbor from a painting by Orlando Boars *

THE FIRES THAT ENDED THE DEPRESSION

On February 18, 1877, the third of Sag Harbor's major conflagrations swept the wharves and business section of the Village, destroying 31 buildings, including the music hall, Nassau House Hotel, the Flour mill (which became the Sag Harbor Grain Company and later Grumman, where parts for the Lunar Landing Module were produced), residences on Rysam Street, and the remaining whaling warehouses. One firefighter’s excerpt gives a vivid picture: “A furious wind and snow storm were raging and the night was bitter cold. The water in the two street wells was soon exhausted and the boys backed the old ‘Minnehaha’ engine into the bay at the slip west of Huntting’s block and stood in freezing water knee deep pumping for dear life, relayed by citizens, as the members dropped out one by one from sheer exhaustion. With little water, meager equipment and exhausted fighting force, the fire raged out of control.” (from American Beauty, by Dorothy Ingersoll Zaykowski)

This fire was followed in 1879 by the Cotton Mill mysteriously burning, which made room for French immigrant and watchcase manufacturer Joseph Fahys to relocate his factory here in 1881. Fahys' factory was the Village’s employment mainstay thereafter until it was closed during the Great Depression, in 1931. The Village leased the second floor to a subsidiary of the Bulova Watch Company, and in 1937 citizens formed a committee to raise money for renovations and new machinery, and production increased to around 30,000 watchcases per week, until Bulova occupied the whole building. This also led to a housing boom between 1885 and 1915, with approximately 80 small factory workers’ houses being built in Sag Harbor.

At its lowest ebb in the mid-1870s, Sag Harbor’s population had dropped to slightly over 2,000. In 1907, the Brooklyn Eagle observed that “Sag Harbor has awakened from its moribund condition that followed the decline of the whaling industry and become a bustling manufacturing village of from 4,500 to 5,000 population, but not as important relatively as fifty years ago.”

Before and After Fire of 1877 †

Remains of Cotton Mill †

Map of 1877 Fire †

Leather Fire Bucket *

THE GREAT WHITE HURRICANE: THE BLIZZARD OF 1888

1888 was marked by a legendary snowstorm, starting the 11th of March and lasting three days, which was nicknamed the “Great White Hurricane". It crippled New England from Chesapeake Bay to Maine. The New York Times described it as “a tornado of wind and snow”. Ships sunk at sea, wires went down, stopping all communication, and transportation was immobilized. Conditions were horrible in Manhattan as well as eastern Long Island. From the New York City Subway’s website, G.J. Christiano wrote:

"One man suffered a gash on his forehead when he fell into a snow drift. The drift was soft and deep, but his head struck the leg of a dead horse buried there. For some time afterward, the man showed his friends the wound and boasted that he was the first person ever kicked by a dead horse...

In the suburbs, the snow drifts reached fantastic heights. A man living on Long Island had to leave his house to buy some needed groceries. He set out on a homemade pair of snowshoes for a store about a mile away. He walked on top of snowdrifts, but did not realize how huge they were. Then he looked down and saw some very tall trees. He realized that the drifts were about sixty feet high!

It was many weeks before the last signs of the deepest snow drifts disappeared. It was reported that one tremendous drift lasted until July!"

And for a description of the blizzard’s effect in Sag Harbor, from the book Voices of Sag Harbor: A Village Remembered (edited by Nina Tobler), is this accounting by Larry Burns, a Sag Harbor native:

"My grandmother, Mary Keating, had a member of her family who was a whaler during the whaling days. She remembered the blizzard of 1888 in SH, which left four to five Ft of snow. It was called the Great Blizzard, and everything was buried under the snow for days. Mary remembered a neighbor of hers who gave birth to a premature baby, named Len Roberts. It was so cold during the storm that the only way to keep the baby warm and alive was to put him in the oven, on one of the grates. He survived and went on to reach 100 years old."

Digging Out the LIRR †

Blizzard Magazine *

Madison Ave after the Blizzard *,

Old Tinted Postcard Making the Most of a Mess †

THE GREAT FIRES OF 1915 AND 1925

There is a curious architectural connection between the Fires of 1915 and 1925. If you look at the first photo here of the aftermath of the "Bikeshop" Fire of 1915, the building to the right of the destroyed building, which was relatively unscathed, was, ironically, the start of the Great Fire of 1925, or the Alvin Silver Fire. The Alvin Silver Company, housed in a huge building just south of Washington St, employed a substantial number of Sag Harbor residents, and its products were renowned.

Again, from Zaykowski’s book American Beauty, we have this account:

“It was a frigid, blustery winter’s night. The residents of Sag Harbor had just ushered in the New Year with celebrations and the customary whistle-blowing at the midnight hour. January 1, 1925 had arrived, and with it another disastrous fire. About 3 AM, fire was discovered in the Ballen Store annex on Washington Street. By 3:30am Ballen’s annex fell to the ground with a crash, sending sparks and embers into the air and onto the roofs of nearby structures. As the blaze progressed, Ballen’s stock of ammunition, shells and cartridges exploded, creating what was described as a scene from a war zone, and sending spectators in all directions. Linemen from the Sag Harbor Electric Light and Power Company climbed the icy poles to cut electric wires and shut off the current. Hoses were placed in holes cut into the ice, at the foot of Main St, and stretched to the scene. It provided an ample supply of water but turned out to be no match for the gale force winds which fanned the flames. Alvin Silver Company’s yellow pine interior caught fire and burned furiously.”

In spite of the cold, the blaze from the Alvin Silver Fire was so intense that windows across Main Street cracked from the great heat. Zaykowski continues:

"The massive brick structure stood doomed. Heat became too intense for the fire fighters to place ladders against the building, and they watched, in disbelief, as the place succumbed in the blaze. For more than 20 years the decorative facade stood, with the wooden panels beneath its graceful arches used for an honor roll to hold the names of those serving in WWII. In 1950 the place was purchased by Bohack and a supermarket built on the site.”

The Alvin Silver Company †

Two Views of the Alvin Company †

Fire and Firemen After the 1915 Fire †

After the Great Fire of 1925 †

THE EARLY DAYS OF THE SAG HARBOR FIRE DEPARTMENT

Sag Harbor has the fined distinction of having the first Fire Department in the State of New York, having been chartered in 1803. Before pump hoses and fire hydrants, all residents of Sag Harbor were expected to keep leather buckets in their households to help form fire brigades, and were fined 50 cents if they were found to be lacking. Fires in wooden buildings, and especially those storing whale oil, were notoriously hard to put out, and it took an especially courageous person, then as now, to tackle them. We offer these wonderful early photos of the Sag Harbor Fire Department to give you a sense of our previous first responders.

Of special note is that William Howard, the Sag Harbor Fire Chief at turn of the 20th C, was also a gifted photographer who provided many of the invaluable historical photographs that grace this tour, as well as many of the Eastville Community Historical Society's “Collective Identity” photographs, featured here in the tour “Eastville Community: Unique Diversity”.

Washington St Firehouse of 1895 †

Hose Demo at Mashashimuet Park †

Church St. Fire House †

Men of the Murray Hill Fire Col †

King Juvenile Hook & Ladder Co, photo by William Howard †

"THE LONG ISLAND EXPRESS": THE GREAT HURRICANE OF 1938

This story of this disaster begins in Africa.

The storm's very first recorded indications were wind shifts, observed by the French in the Sahara Desert on September 4th, at Bilma Oasis. As the disturbance moved west off the African coast, it picked up tremendous speed, and by September 16th a Brazilian freighter in the Atlantic reported weathering winds of 74 mph or faster, hurricane force. Storm warnings were issued in Florida, but the storm seemed to turn and it was thought that it would peter out in the mid-Atlantic.

Even the best forecasters were fooled by the speed of this storm. Across New England there had been prior rainfall, and streams and rivers were full to their banks. The tide was already extremely high, it being the autumnal equinox. As the storm swept by the coast at winds greater than 60mph, twice as fast as normal, it tore up parts of Atlantic City’s boardwalk.

By this time the eye of the storm was 50 miles wide, and it continued northward into New England at more than 50mph, hardly slowing down as it hit land. It arrived here on Wednesday, September 21, at about 2:30pm. When the hurricane and its tidal surge hit Long Island, and its impact registered on seismographs in Alaska. The east side of the vortex had speeds approaching 100mph, with gusts measured in Long Island Sound at 120mph.

A letter quoted by his wife Dorothea in famous weatherman Richard Hendrickson’s book Paumanok: Winds of the Fish’s Tail, recounts trying to get home from work in Bridgehampton and the following day:

“You never saw such a mess in your life… Lumber Lane was a mass of fallen trees. I climbed over at least 15 monsters to get home. Most of them I had to climb up, sit on, and slide down the other side, because the trunks were so huge…Thursday we did a little driving around. The wrecked houses, barns, churches, and the trees down are a pathetic sight… I got through to Sag Harbor to deliver my food orders Thursday afternoon. It was 13 miles instead of the usual 4 from my house… The beautiful steeple of the Presbyterian Church… is shattered. At its top used to hang the light which guided the whaling vessels back to their home port. A light was always kept burning there even in recent years. That’s one landmark that will be missed terribly around here… The whole town of Sag Harbor is terribly wrecked. The Methodist Church Steeple toppled over on to the back end of the house of one of my relief clients. That same house is smashed in in front by a huge tree which also smashed the son’s car. I suppose you’ve heard about the tidal wave at West Hampton Beach. That Mrs. John King that was drowned was a very good friend of the Hendricksons’..."

Dune Road in Westhampton was almost totally devastated, and as noted in almost every account of the storm, the loss of the massive 185 ft steeple from Sag Harbor’s National Historic Landmark, the First Presbyterian (Old Whalers’) Church, quickly became a hallmark of its destructive force.The storm's aftermath can still be seen, in a sense, because the Old Whalers' Church steeple, beacon of homecoming to citizens and sailors out at sea since 1844, was never rebuilt. Ironically, Minard Lafever, architect of the church, had built it with the possibility of devastating storms in mind, and had left a clever gap between the base of the church and its steeple for the wind to pass beneath. Parishioners found the moaning of the wind through the gap distracting and stuffed the gap, sealing its destruction during the Long Island Express and also causing it to collapse numerous tombstones in the Old Burying Ground beneath it.

The hurricane was estimated to have killed 682 people, damaged or destroyed 57,000 homes, and caused property losses estimated at the equivalent of $4.7 billion today. As terrifying as Superstorm Sandy was, for Sag Harbor the Long Island Express still bears the dubious honor of being our most devastating storm.

Old Whalers’ Afterwards †

Destruction on Main St †

The Old Whalers’ Church Steeple Before the Long Island Express †

RECENT DISASTERS, AND THANKS TO OUR AMBULANCE CORPS AND POLICE DEPARTMENT

We haven’t been unscathed since the Long Island Express made landfall here. In 1954 Hurricane Carol, a category 3 hurricane, caused devastation in the Northeast, and was followed by lesser hurricanes Donna (1960), Gloria (1985), Bob (1991), and then Superstorm Sandy in 2012, which killed 5 people in the northeast and left power out for days for most of us. Quite a powerhouse. Fires have not been so frequent, as safety precautions and fire-fighting techniques have improved, but there was, of note, the Saint Andrews Church Fire in August, 1965, and in 1994 the Easter Fire on Main Street, mostly affecting the Emporium Hardware store and Marty’s Barber Shop, a well-loved fixture of the village. Both had to be rebuilt. As the New York Times reported, "The building north of the store, though severely damaged, remained standing. Its owner, Marty Trunzo, had been cutting hair on the ground floor for 54 years in his barbershop.”

The building also housed a camera shop, an apartment and two offices, including one where Thomas Harris wrote much of 'Silence of the Lambs.’” Besides running Marty’s Barber Shop, Mr. Trunzo helped start the Firemen’s Museum and had himself been a volunteer fireman for most of his long life.

After Superstorm Sandy, the Sag Harbor Volunteer Ambulance Corps received a special proclamation from the Suffolk County Legislator for their heroic work in its aftermath. The Ambulance Corps had immediately rushed to assist the Broad Channel Fire Department of Queens, NY, which had lost its entire fleet due to flooding. It filled a retired 2002 ambulance with donations from local residents, organized by Sag Harbor Village Police Chief Tom Fabiano, which included clothing, food, toiletries, and a check in the amount of $1200 to assist in Broad Channel’s recovery efforts. The Corps not only delivered the goods, but left the retired ambulance to the Broad Channel’s department. Our hats are off to our Ambulance Corps and Police Department.

St Andrews Church Fire †

Flood from Superstorm Sandy ‡

Hurricane Carol, 1954 *

Proclamation to Ambulance Corps §

THE FIREMEN’S MUSEUM AND THE SHFD TODAY

We must end this tour by honoring the truly extraordinary Sag Harbor Volunteer Fire Department. Its history is commemorated in its Firemen’s Museum at the corner of Church and Sage St. The Department consists of 5 Companies: Gazelle Hose Co. No. 1, Montauk Hose Co. No. 2, Otter Hose Co. No. 3, Murray Hill Hose Co. No. 4, and Phoenix Hook & Ladder Co. No. 1. The department has 3 Squads: Heavy Rescue; Fire Police, and a Dive/Water Rescue Team. The SHFD actively engages in the community and teaches children how to prevent and handle fires.

The Murray Hill Fire House at Elizabeth and Division Streets is one of the oldest firehouses in the country (1893). The Sag Harbor Firehouse that now houses the museum at 46 Church St was, before 1896, variously a schoolhouse, voting hall, jail, and finally a garage for the SHFD’s Hounds Engine Company No. 2. A bay was added in the late 1800s for the Gazelle Hose Company, founded in 1853, after its fire house (ironically) burned down. Fire trucks were moved to modern quarters in 1976, at which time Thomas W. Horn Sr., long a volunteer fireman and former fire chief, organized a group of volunteers to create the Museum. It is full of fascinating artifacts: “Comb” hats, heavy old helmets whose brims looked like coxcombs, many vintage photographs, the leather buckets every house had to have for participating in fire brigades, a silver “foreman’s trumpet”, used like a megaphone to shout orders during a fire, and much, much more.

A mural depicting the fires of 1915 and 1925 is on one wall downstairs, and on another a wood Honor Roll plaque honoring firefighters who didn’t return from WWII. The centerpiece of the museum is the 1926 Ford Model T fire chief’s truck on the ground floor. The museum is unique in that visitors are invited to touch everything! It’s open on weekends in the summer, and by appointment for groups by calling 631-725-0779.

Firemen’s Museum ‡

Murray Hill Fire House ‡

Mural of 1915 and 1925 Fires ‡