Vanished Sag Harbor

Vanished Sag Harbor will take you on a largely virtual tour of things no longer with us, but to places and people of exceptional historical interest.

It will cover time from the beginning of the whaling industry and all it brought to our history to the building of parts for the Lunar Landing Module, and celebrate the curious as well as the courageous.

You'll find many surprises on this tour!

.

Turning Dirt into Money

When Sag Harbor was in its financial heyday during the whaling boom of the early to late-1800s, grand mansions were being built and townspeople were settling in for a seemingly never-ending expansion of riches and economic possibilities.

Ironically, it was at first exceedingly difficult to get from Sag Harbor to the other old towns, Bridgehampton, East Hampton and Southampton, that lay along the ocean coast and where the main road lay. The dirt path that joined Bridgehampton and Sag Harbor was in fact constantly needing to be hacked clear of brush and foliage, and there was a similarly difficult road that joined Sag Harbor to East Hampton. Because the paths were dirt, of course there were also washouts and ruts, treacherous to the wagons that plied them.

Seeing opportunity in this, three men, Samuel L’Hommedieu Jr. and William R. Sleight of Sag Harbor and Abraham T. Rose of Bridgehampton approached the State Legislature in Albany in 1833 for permission to build a toll road between Sag Harbor and Bridgehampton. They were granted permission the same year and called their company the Sag Harbor and Bull’s Head Turnpike Company, after the section of Bridgehampton known as Bull’s Head (where the war memorial is today), from which the road connected with the outskirts of Sag Harbor at Otter Pond. They sold shares of their new $4,000 company to the public at $20 each.

The Turnpike opened in 1837 and began to collect revenue, charging 8 cents per 2-horse wagon, 12 cents per stagecoach, 4 cents for sleds or sleighs drawn by one horse, ox or mule, 3 cents for horse and rider, 2 cents per additional horse, mule or ox, and various other fees for scores of cattle, sheep and hogs. The tollhouse, where the toll master’s family lived, was a house built on the west side of the road.

The venture was so successful that four years after it began, a second toll road was opened between Sag Harbor and East Hampton, in 1844. The company took a hit when the Long Island Railroad opened a spur to Bridgehampton and then on to Sag Harbor in 1870, but continued until 1901, at which time it stopped taking tolls, and shortly afterwards the tollhouse to East Hampton was similarly abandoned.

Of course the real problem was the sudden lack of prosperity in Sag Harbor as the whaling industry ground to a close, but that’s the topic for whole other aspect of Vanished Sag Harbor.

Map of Toll Houses

The Sag Harbor/Bridgehampton Turnpike Toll House

.

The Sag Harbor Railroad Branch

The railroad spur that was built from Bridgehampton to Sag Harbor began in 1870, at what was still the heyday of the whaling industry. The line was actually conceived and surveyed in 1854, and Sag Harbor remained the furthest point east for the railroad until 1895, when the LIRR extended the railroad to Montauk. This left Sag Harbor a spur of the line, and a new station called “Lamb’s Corner” was opened in Sag Harbor in 1906, later renamed “Noyack Road”. Commerce into and out of Sag Harbor declined with the whaling industry. In fact, by 1895 only four ports, not including Sag Harbor were sending out whaling ships.

Eventually a freight spur was built to reinforce the tracks into Sag Harbor for munitions testing, but in general the decline of the spur was inevitable. The Railroad was also the subject of certain ridicule, there being so many accidents that it was accused of “trying to control the population” in the press. On August 9, 1890, five of seven train cars derailed. Between 1872 and ’73, four cows were run over by trains, which led to its nickname “The Slaughterhouse on Wheels”. To this day pieces of “iron horse manure” (debris left over from unburnable coal) can be found along where the tracks had been.

On May 3, 1939, the Sag Harbor branch was officially abandoned, rail service ended, and the steel tracks began to be torn up for use in World War II.

Photos courtesy of the Sag Harbor Historical Society of the Sag Harbor Branch of the Long Island Railroad

From the Earth to the Moons

There is still today a large brick building near Long Wharf that was originally the Sag Harbor Grain Company, dating from 1879. Children would play in the giant piles of grain stored there, and of course the railroad spur to Bridgehampton was used to transport it, but it was taken over by the E.W. Bliss Company around 1890.

The E.W. Bliss Company had a munitions factory in Brooklyn and established this building for administering the testing of its torpedoes before and during World War I. The testing was done at Long Beach and Gardiner's Bay, and there is still a Bliss Torpedo Testing Station Corner Stone, dated 1891-1925, visible here.

As a result of the testing, Long Wharf had to be reinforced with concrete and rail spurs, the torpedoes being shipped through Long Island via the Bridgehampton-Sag Harbor railroad branch and then out to the Wharf. Inventor Thomas Alva Edison was one who observed the testing of these torpedoes, and divers have since found torpedo shells on the bay floor.

Later, this building was occupied by both Agwam Aircraft Products, which build jet parts here, and by the Grumman Aerospace Corporation, which built components of the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM).

Agwan Aircraft Manufacturing

Sag Harbor Granary*

E. W. Bliss Torpedo

Grumman Lunar Landing Module

Eastville and The Underground Railroad

Although little is sure about Eastville’s participation in the Underground Railroad, some evidence suggests that it may have played a part. Eastville was, and remains, a uniquely diverse community, with Irish, Native American and African American residents who all lived here in the 1800s, many of whom worked in the whaling industry [see the Eastville tour on this app]. Lyman Beecher, Harriet Beecher’s father, preached in Sag Harbor. One of the St. David African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Zion Church’s first preachers, J. P. Thompson, was a known abolitionist. The Church, which was the principal church for the community, has two trap doors, one by the pulpit and one under the library, near the rear of the church, that have been suspected to be connected to the Underground Railroad. The type of people who populated Sag Harbor during the mid-1800s, who included Quakers and abolitionists, were also possible contributors to the anti-slavery effort.

When people think of slaves escaping from the South before, during and after the Civil War, the image one often has, thanks to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, is that of people wading through swamps to their freedom, but it must be noted that many such people were not only leaving the South itself, but would have been escaping from owners whom they had accompanied to places in the Northeast, or whose owners may have moved here with them. Historians of the Eastville Community Historical Society believe that Native Americans could have helped such slaves to freedom, using their hunting and fishing routes and their guiding expertise. One such route existed from the Shinnecock Nation lands to upstate New York, which, though not having trap doors and hidden passageways, would have been just as important in assisting people to freedom.

As well as footpaths Native Americans would be familiar with, boats that docked in Sag Harbor could have transported runaway slaves up to Connecticut and Rhode Island, where they would also have been able to travel on foot to freedom in Canada.

Homes on “Liberty" Street, as well as on Hempstead Avenue, feature hidden trap doors that lead to gritty old cellars. Of course it’s possible that these were only used for cold storage, but the question of their use persists. Hempstead Avenue—named after the Hempstead family, known for being slaveholders on Long Island—also features similar houses. A number of families owned slaves on Shelter Island, and its proximity to Sag Harbor would have meant a need for freedom for captive people in our area.

Because of the necessity for secrecy of the Underground Railroad, and the long period of time in which it functioned, historians here have been unable to find definitive proof of it, but there are certainly many indications of its possible presence in Sag Harbor.

Trap Door in Church #

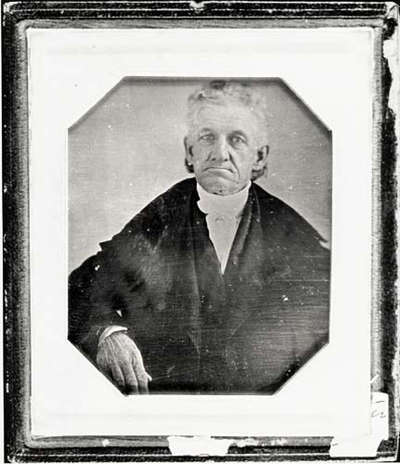

Lyman Beecher

St David AME Zion Church #

Grave of David Hempstead §

We Are Still Here

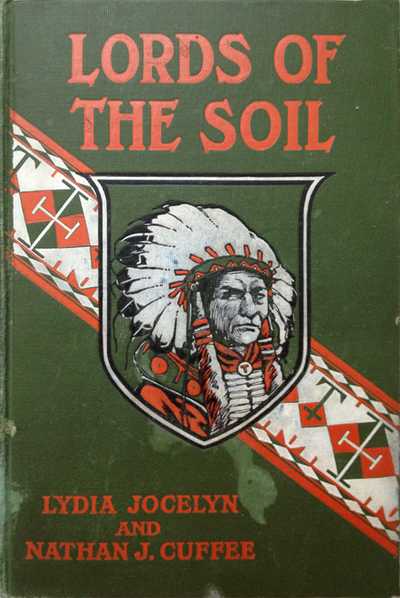

Nathan J. Cuffee (1854-1912) was born in East Hampton to whaler Jason James Cuffee, a member of the Eastville Band of the Montaukett tribe, and Louisa R. Cotton of the Naragansett tribe from Rhode Island. Nathan also grew up here in Sag Harbor on Liberty Street, and later moved with his wife Marie to Shelter Island. Cuffee co-authored a novel with Lydia Jocelyn called Lords of the Soil: A Romance of Indian Life Among Early English Settlers in 1905 which was well-received, making Cuffee the first published Native American from Long Island.

Perhaps the best-known name in Montaukett local history is Pharaoh, a long and distinguished family, some of whom now reside in Sag Harbor in the Eastville area.

At the end of the 19th century, the most famous Montaukett was Stephen Talkhouse (Stephen Taukus “Talkhouse” Pharaoh, 1821-1879). He was known to walk 30 to 50 miles round-trip per day from Montauk to East Hampton or Sag Harbor. Legend has it that he walked in one day from Brooklyn to Montauk. Various stones on his routes mark the present-day Paumanok Path hiking trail.

A sad bit of history is that P.T. Barnum hired Stephen Pharaoh and featured him as "The World's Greatest Walker", and the "Last King of the Montauks", despite his being neither a king nor the last Montaukett. The Montauketts were in fact run out of their lands, and were forced to settle in Eastville and other further-flung areas, fracturing their communal living and creating a disjointed society that has hindered them from gaining federal recognition. The 2013 Montaukett Act in the New York Legislature reversed a century-old state declaration that had declared them to be extinct, and they are still fighting for proper recognition.

Members of the Montauketts

Stephen Talkhouse

Lords of the Soil

Nathan Cuffee #

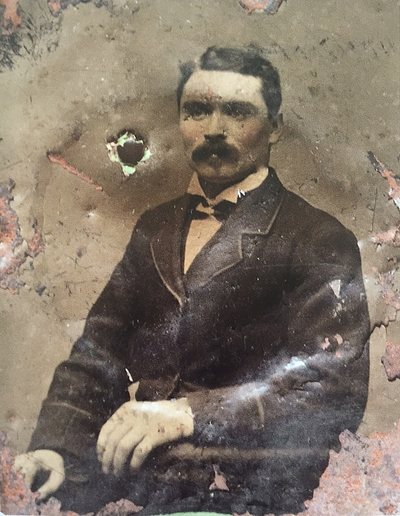

Frank Pharaoh

Prentice Mulford: Thoughts are Things

What is now the Municipal Building on Main Street used to be the "Mansion House Hotel”. Philosopher and humorist Prentice Mulford (1834-1891) was born there, and the building was owned by his father. The present brick building replaced it after the disastrous fire of 1845.

Mulford was said to have been very strange. He foresaw the airplane and radio and prophesied mental telepathy, so perhaps it’s not surprising that Mulford founded a philosophy called “New Thought”, which still has a following, and he published a guide to it called “Thoughts Are Things”. Mulford moved to California where he spent several years in mining towns, then became known as part of the San Franciscan “Bohemians”, partly for his disregard of money. He was a prolific writer, editor and lecturer, returning to New York City is 1872.

While in England as a guest lecturer, he met a young woman who may have been a prostitute. He brought her back to New York City but later found her photographed on a French Postcard included in pack of cigarettes he'd purchased. Despondent, he moved to the Seacaucus swamps in New Jersey, lived in rags, & wrote philosophy. Presumably coming back to Sag Harbor to visit his two sisters (who still lived on Madison Street, and ran a small school there), he had a stroke and was found dead, floating in the water. He is buried in Oakland Cemetery, marked only by a stone that says, “Thoughts are Things”.

Mulford’s Birthplace

"Thoughts Are Things" by Prentice Mulford

Getting High on the Old Whalers' Church Steeple

George Sterling (1869-1926) was born towards the end of the whaling boom. Sterling’s father was Catholic, and Sterling was a mischievous and difficult child in his father’s eyes. His most notorious prank was climbing and running up a pirate flag on the First Presbyterian Old Whalers' Church's steeple, which was 185 ft. taller than the present church and visible from far out at sea.

Sterling was eventually remaindered to his uncle, Frank C. Havens, who lived in the Bay Area of San Francisco, in 1890. Sterling became a poet there and was eventually made Poet Laureate of California. He was friends with Upton Sinclair, Jack London, Ambrose Bierce, Brett Hart, and Mark Twain.

He was nicknamed the “King of Bohemia” by his set, was alcoholic and depressive, and (not surprisingly) had a failed marriage. One anecdote cites that he was put in charge of the wine for an upcoming party of writers, but drank it all before the party. Sterling carried a vial of cyanide in a ring, and eventually swallowed it, committing suicide in 1926. He was compared to Euripides & Shelley, and his poem "A Wine of Wizardry" was thought to have been "the greatest poem ever written by an American author”.

The steeple George climbed as a child on the Old Whalers’ Church, as mentioned, was a notable landmark in the village. The church was built by Minard Lafever in 1844 in the "Egyptian Revival" style, and is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. But the steeple itself also functioned as an important beacon for sailors, being the first thing visible of home when they returned from long, arduous voyages to the other side of the world.

In 1938 it was knocked clean off by the “Long Island Express”, as the Hurricane of 1938 was nicknamed, into the graveyard below. Its loss has been much lamented, but it was never rebuilt. The same hurricane also tossed off the steeple of the Methodist Church, which lies just south of Main Street (now a private residence).

Old Whalers’ Today‡

Sterling in CA

Church After Long Island Expres

Old Whalers’ Before 1938

George Sterling

The Alvin Silver Company and the Great Fire of 1925

From 1911 till January 1, 1925, the Alvin Silver Company was the Village's largest employer, besides the Fahys Watchcase Factory. Alvin Silver Manufacturing was originally headquartered in Irvington, New Jersey in 1886, and then changed to Sag Harbor. The company was purchased by Joseph Fahys in 1897.

American manufacturers quickly became prolific purveyors after the discovery of silver reserves in mines in Nevada. The Alvin Silver Company had an enormous building right on Main Street not far from the Watchcase Factory, and produced fine flatware and hollowware. Many of its patterns produced here were historical, and its dies were purchased in 1928 by the Gorham Company of Providence, RI. The Alvin Silver building was gutted and lost in the New Year’s Day fire of 1925, and is depicted in a large mural in the Firemen’s Museum, at the corner Church and Sage Streets, commemorating the courage of the firefighters in that horrible conflagration.

Alvin Silver flatware and hollowware is still very desirable for collection, and you’ll see a beautiful spoon (on temporary loan at the Sag Harbor Historical Society) commemorating the Old Whalers’ Church, complete with still-extant steeple, in an accompanying photo.

Alvin Silver Co., qua Post Office in Its Heyday*

Alvin Silver Museum after the Fires of 1925*

Great Fire of 1925 Depicted in Firemen’s Museum

Example of Flatware with Old Whalers’*

The Performance That Brought the House Down

At the northeast corner of Sage and Church Streets, a sign designates the original site of the Sag Harbor’s first real theater. The Atheneum was very popular in the Village at the turn of the last century. It variously hosted the Masons, dances, basketball games, and even sported – no pun intended – a bowling alley in its basement.

The Atheneum is another Sag Harbor edifice that burned to the ground and was never rebuilt. One notorious story is from a woman who was at its demise, Anita Miles Shelton Anderson, pictured here. By her own admission she said that the performance she gave the night before the theater burned down on April 30, 1924, was so “hot" that it was thought to be to blame for starting the fire. For her performance that evening, she had decided to do an “Oriental" dance, wearing a “bra of gold cloth, and the skirt was long black chiffon, which was banded in gold."

“While we were practicing I said, 'Turn out the footlights when I come out to dance’. Well, they didn’t turn out the footlights, and when I came out to dance, the footlights practically took my skirt right off me… That night, the Atheneum burned down, and I never lived it down. They all said that I set the Atheneum on fire." (–from Voices of Sag Harbor: A Village Remembered, 2007, Edited by Nina Tobier)

One can only imagine the see-through effect of those footlights in 1924! Ms. Anderson died on April 7, 2005, at the age of 100.

The Atheneum was beloved and its loss mourned by Sag Harborites, who then turned to Guild Hall, in East Hampton, for their theatrical satisfaction. Now, of course, we’re lucky to have Bay Street Theater in our midst.

Anita Anderson Performing*

Thanksgiving Performance at the Atheneum*

The Atheneum*

A Lost Industry and the Whaling Museum

By 1820, sailors, slaves, harpooners and exotic people from foreign lands, speaking exotic languages, rubbed shoulders in Sag Harbor. Slavery existed here and on Shelter Island, and was not declared illegal in New York State until 1827. Sag Harbor was known for its lawlessness, and was cited by Herman Melville in Moby Dick for it, when Queequeg decides to remain a pagan in light of the way he sees Christians comporting themselves in “old Sag Harbor” and Nantucket. At the height of the whaling industry, 60 whaling ships made Long Wharf their home port, often traveling to the other side of the world in search of the oil that made their captains and boat owners staggeringly wealthy. James Fenimore Cooper stayed at the Duke Forham Inn, a stone’s throw from Long Wharf, and was inspired to write his first novel, Precaution, there. His Leatherstocking Tales character Natty Bumppo was inspired by Sag Harbor whaling boat captain David Hand.

The whaling trade was unusually tolerant of hiring Native Americans and African Americans, some of whom became captains. A boat called the Industry, sailing in 1822, had an all-black crew. Whales had been plentiful in New England waters before the industry decimated them here and abroad, with hundreds of thousands killed mostly for their oil. The business's expansion happened just prior to the American Revolution, stalled during the war, and then thrived more than ever. In 1858 the American whaling fleet numbered 199 ships. In 1859, however, decline became inevitable with the discovery of petroleum at Oil Creek, Pennsylvania, and by 1895 only four US ports were sending out whaling vessels, Sag Harbor already having stopped.

As you walk down Main Street, you’ll encounter many whaling captains' mansions built at the height of the industry, many with widows’ walks with which to view the harbor, and many ornately decorated [see the Sag Harbor Historical Society’s tour for its most prestigious mansions]. None was perhaps more ostentatious and in many ways more fantastical than that commissioned by whaling Captain Benjamin Huntting II. Huntting hired Minard Lafever, who was finishing up the Old Whaler's Church around the corner, to design a classic, Greek temple-front mansion. It later became the summer home of Mrs. Russell Sage, in 1867, then a home for the Masons, and finally the Sag Harbor Whaling and Historical Museum in 1936. The building sports fluted Corinthian columns, blubber-spade decorations along its roofline, and you must pass through enormous whale jawbones when entering the front door, all lauding the success of its first owner.

The museum is now dedicated to cetaceous studies, and celebrates both the history of Sag Harbor and the importance of environmental awareness and species’ protection. The Museum is open 7 days a week and well worth a visit.

Hannibal French House ‡

Whaling and Historical Museum Interior §

Sag Harbor Whaling and Historical Museum ‡

Whaling Crew (photo courtesy Bedford Whaling Museum)

Stand-Off at the L’Hommedieu House

The L’Hommedieu House is where brothers Oliver and Jared Wade Jr. held out for a week with harpoon guns aimed at a mob outside it.

The story is this: While the Civil War raged, it became more and more difficult to attract volunteers to the Army. Men who had families were reluctant to leave them, and of course casualties were staggering. In response, towns offered cash to enlistees. East Hampton, for example, offered $400 to each man who volunteered, plus a whopping $3 per month to his wife and $1 to each child. However, not every town was able to meet its quota, and in 1863 the Federal Government issued a draft. The first draft selection in New York in July 1863 resulted in tremendous riots in the City which spilled over into Long Island. Lisa Donneson’s Guide to Sag Harbor Landmarks describes that in Sag Harbor Oliver Wade, having heard that threats were being made against the African-American residents of Eastville (since African-Americans were blamed for the war by many), found rifles and distributed them among the Eastville residents for their protection. He was then threatened himself, so he holed himself up in the L’Hommedieu House armed with harpoon guns fitted with iron slugs, ready to protect himself. Luckily, no fighting ensued and after a week everything returned to normal. Oliver spent most of his adult life in this house.

George McClellan, Lincoln’s Democratic opponent, vacationed in Sag Harbor and East Hampton in the summer of 1863, and was well-liked, but In spite of the rancor caused by the draft and resentment of the war, in the election of 1864 the normally Democrat-leaning town of East Hampton had elected Lincoln by eight votes.

You’ll notice that this house looks more like a New York brownstone than the other houses of Sag Harbor. Samuel L’Hommedieu built it c. 1840, in anticipation that Sag Harbor, home of the booming whaling industry, would soon be as densely populated as New York City. Samuel L’Hommedieu himself was the grandson of a Huguenot fugitive, Captain Ephraim L’Hommedieu, a Revolutionary War veteran now buried in the Old Burying Ground above the Old Whalers' Church. Samuel operated a ropewalk, a long narrow building where workers walked back & forth twisting hemp into rope for use in ship’s riggings, line and cables. The ropewalk was situated in nearby Peter’s Green, just off Glover Street.

L’Hommedieu House*

Harpoon Gun of 1800s

Grave of Ephraim L’Hommedieu §

The Ponies vs the Philanthropist

In 1874, what is now Mashashimuet Park was the Hamptons Driving Park and Fair, and by 1879 a half-mile oval track was built for carriage team races, trotting, and walking races. You can see the festive atmosphere in the old photo shown here, and it must have been quite a draw. The park’s popularity showed in its new name: Sag Harbor, Hampton and Shelter Island Park and Fair Grounds. It even expanded with an exhibition building built for judging produce, poultry, flowers and baked goods, although that building was destroyed by one of Sag Harbor’s many fires in 1890.

In 1893 the Great Bicycle Tournament attracted over 1,000 spectators, but sadly, by 1900 the park grounds began to deteriorate.

Enter Mrs. Olivia Slocum Sage (1828-1918). Her inherited fortune was from her husband, Russell Sage, who made a killing in the unregulated stock market. Mrs. Russell Sage had great affection for Sag Harbor, the childhood home of her mother, and purchased the Huntting House, now the Sag Harbor Whaling and Historical Museum, after his death in 1906, spending her summers there between 1908 and 1912. Mrs. Sage was an ardent philanthropist and particularly sought to help the many poor immigrants employed at Fahys Watchcase Factory. In 1908 she bought and decided to refit the Sag Harbor Park and Fair Grounds with “scientifically designed” equipment and amenities, hoping to convert it from its vulgar amusements to those more uplifting. There were, for instance, 114 plots for children’s gardens, and weekly band concerts. In 1910 she also purchased the lands surrounding Otter Pond to add to the Park property, and moved 13 houses off the land to give to needy families. Mrs. Sage also underwrote edifying activities like lectures and folk-dancing for the Atheneum Theater (see The Performance That Brought the House Down).

Pierson High School was another project of Mrs. Sage’s, constructed at the same time, and its name commemorated her ancestor Abraham Pierson, first rector of Yale University in 1702. Finally, she was principal benefactor of a new domed building which became the John Jermain Memorial Library, named for a local successful merchant who was her grandfather.

Mrs. Sage’s generosity was not entirely appreciated by the community, and Mrs. Sage abandoned her manse in anger in 1912 after discovering that contractors for Pierson High School had cheated her by using cheap construction materials rather than those she had paid for. There were also reports of vandalism against fixtures in her park. She did allow William Wallace Tooker, self-trained ethnologist and “Algonkinist”, to rename the park in 1908 with the Algonquin name Mashashimuet, meaning “Place of the Great Springs”, the name it still enjoys today.

Mrs. Sage

Whaling Museum‡

Pierson High*

The JJML Library*

The Park*

The Old Racetrack*