WORKING SAG HARBOR

Welcome to Working Sag Harbor, an introduction to the occupations that have helped define Sag Harbor over the years. Colonial agriculture on eastern Long Island grew quickly, and by 1770 we were a village of 35 dwellings. Trade with the West Indies made the “Harbor of Sagg" a significant seaport, and with a stage route established to New York City, Sag Harbor quickly became a hub for trade and transportation. But first, we must start with its even earlier history.

.

Wegwagonuck: Indigenous Sag Harbor

Long Island and southern New England was inhabited by Algonquins, who were related by language but had distinct cultural differences. Algonquin peoples in and around Sag Harbor were farmers and fishermen, and whalers. This area was originally known as Wegwagonuck (a phonetic spelling invented by William Wallace Tooker (1848-1917), a self-styled “Algonkinist”, used in his 1896 article on Sag Harbor). Wegwagonuck means “place at the end of the hill” and the name “Sag” refers to one of the first crops that was sent back to England, sagabon, a tuber-producing vine now called Apios americana.

Native peoples of Long Island made wampompeag (wampum), shell beads strung onto threads that were used as currency, for record-keeping, and for aesthetic purposes. These shell beads have been found at Native American-inhabited sites as far west as the Rocky Mountains, and it is thought that the wampum made by Long Islanders was the finest. Paumanock was the original name of Long Island, meaning “The Island that Pays Tribute”. The Algonquins on Paumanock were relatively peaceful, and Europeans quickly learned the value of wampompeag in trade with other tribes.

The specific language-based peoples in our area are the Shinnecock and Montaukett, and since the decline of their populations due to dirty dealings by settlers and the spread of infectious disease, which wiped out nearly two thirds of the indigenous people on the island by the mid-1600s, they are still fighting for complete governmental acknowledgment of their identities. Things have fared better for the Shinnecock than the Montaukett in this regard, as the Montaukett suffered a diaspora when their lands were sold by colonial investors, calling themselves the “Proprietors of Montauk”, to New York industrialist Arthur Benson in 1879, who kept the land largely intact for hunting and fishing. The remaining Montauketts were urged to resettle to an upstate reservation. The 2013 Montaukett Act in the New York Legislature reversed a century-old state declaration that had declared them to be extinct, and they are still fighting for proper recognition.

Some Shinnecock intermarried with local colonists and African-Americans, and worked on farms and as craftsmen. They often reared their children as Shinnecock, maintaining their identity and culture.

Gathering of Montauketts

Map of Algonquin Language Areas

Algonquin Wigwam (Library of Congress)

Algonquin in Winter Dress

.

The Whaling Industry

When President George Washington approved the creation of Sag Harbor as a Port of Entry in 1789, the Village had more tons of square-rigged vessels engaged in commerce than New York City. But its riches were really gained during its years as a whaling port, from 1760-1850.

Whales were hunted for many uses, but principally for oil. Sperm oil was used for lubricating machinery and had superior burning properties, producing little smoke or odor. Soap was a byproduct. Spermaceti, the liquid wax from the head of sperm whales, was used to make candles and provided the standard for photometric measurements. It was considered medicinal and used as sizing in wool combing, for leather tanning, cosmetics, and in the manufacture of typewriter ribbons. Non-sperm whale oil was of lesser quality and its use for illumination and food hearkens back to medieval times. Baleen, the long cartilaginous strips many whales have instead of teeth, was used for corsets, buggy whips, carriage springs, fishing poles, and umbrella ribs. Ambergris, the rarest substance from whales, was found in the intestines of sickly sperm whales and was used as an aphrodisiac, in incense and medicine, and in perfume manufacture because of its ability to homogenousely bind the various ingredients used. None of these uses seem a good enough excuse to kill these majestic, highly intelligent beings now, but at the time their killing was routine and thought to be essential for civilized life.

The Broken Mast Monument in Oakland Cemetery shows how dangerous whaling was. As whaling populations diminished worldwide, Japan and surrounding waters were seen as the salvation of the whale hunt. In 1845, the year Commodore Perry first arrived in Japan, Sag Harbor was the still busiest port next to New Bedford, Nantucket, and New London, and its fleet peaked at 63 vessels. By then the average voyage to the other side of the world averaged three years. Whaling attracted fortune-seekers, but also dreamers, romantics, and melancholy men looking for adventure. Many were hayseeds who arrived in buckskin shirts and coonskin hats. At the time, Sag Harbor’s population included Portugese, Spaniards from South America, Maoris from New Zealand, Kanakas from the Sandwich Islands, convicts, and even cannibals from the Fijis, like Melville’s character Queequeg in Moby-Dick. Many of the best whalers were native Americans and African Americans, and many crews hired them as a majority. It was said that no ships left Eastern Long Island without at least one Shinnecock aboard.

Mercator Cooper arrived in Japan on April 18, 1845, on the first ship to visit Tokyo Bay, bringing shipwrecked Japanese sailors home. There they were met by 3,000 armed Japanese. On board were Pyrrhus Concer, an African American who had lived in Sag Harbor, and a Shinnecock named Eleazar. Concer and Eleazar were instrumental in smoothing introductions, as the Japanese were fiercely isolationist and at first threatening to Cooper and his ship in spite of their good deed, but they became intensely curious and somewhat distracted in meeting these two exotic men. They sent Cooper’s ship the Manhattan off with provisions and a warning never to return.

The whaling industry, forced to make such long voyages, suffered a rapid decline after 1846. Winters were stormy in 1847 and 1848, and steamships were beginning to replace sailing vessels. The discovery of kerosene in 1847, the gold rush of 1848, and the discovery of petroleum in Titusville, Pennsylvania in 1859 effectively ended the trade.The last whaleship, the Myra, sailed from Sag Harbor in 1871.

It was in the mid-1800s that many of the more elaborate and impressive houses of Sag Harbor were constructed by successful whaling captains and ship owners, many of which are represented in our "Cornices & Pilasters" tour, and be sure to visit the Sag Harbor Whaling and Historical Museum at 200 Main St for a real treasure trove of history.

Whaling Painting by "Cappy" Amundsen

Whaling Crew from New Bedford Whaling Museum

House Built by Whaling & Shipping Magnate Hannibal French

Tools of the Whaling Trade from the Whaling Museum

Broken Mast Monument in Oakland Cemetery

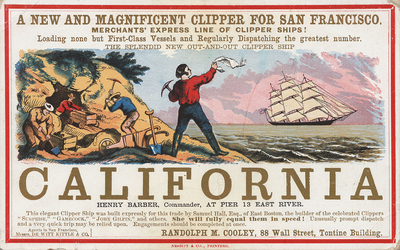

The Gold Rush and the Demise of Whaling

Many whaling ships from Sag Harbor which sailed to San Francisco were simply abandoned during the California Gold Rush. Whaling ships were refitted to take passengers and goods to California to start new lives. Abandonment was such a pressing issue that in December, 1849 a circular was issued out of Nantucket with the notice “...for the perusal of Master of Whalers in the Pacific” to a George Starbuck. It had been a letter written by Frances Coffin in the South Pacific, who wrote, "Firstly I see so many of our townsmen going headlong to the devil, I would willingly stop them if I could... I saw captain Miller, and asked him what he intended to do, he said he should sell his oil, and casks, and all other traps and take freight for California …” Coffin advised Miller not to abandon his journey but to no avail, and reported on other whaling ships being abandoned.

From a lengthy report by Fish and Fisheries Commissioner Alexander Starbuck on the History of the American Whale Fishery, written in 1878:

"Again, during the later days of whaling, more particularly immediately after the discovery of the gold mines in California, desertions from the ships were numerous and often causeless, generally in such numbers as to seriously cripple the efficiency of the ship. In this way large numbers of voyages were broken up and hundreds of thousands of dollars were sunk by the owners. During a portion of the time many ships were fired by their refractory and mutinous crews, some of them completely destroyed, others damaged in amounts varying from a few hundred to several thousand dollars. Crews would apparently ship simply as a cheap manner of reaching the gold mines, and a ship's company often embraced among its number desperadoes from various nations... In order to recruit, it became necessary, particularly during the ten years next succeeding the opening of the gold mines, to offer heavy advance-wages, and too often these were paid to a set of bounty jumpers, …who only waited the time when the ship made another port to clandestinely dissolve connection with her and hold themselves in readiness for the next ship. Unquestionably there were times when men were forced to desert to save their lives from the impositions and severity of brutal captains, but such cases were undoubtedly very rare… There were times, when the California fever was at its highest, that the desertions did not stop with the men, but officers and even captains seem to vie with the crew in defrauding the men from whose hands they had received the property to hold in charge and increase in value."

One of our Sag Harbor literary lions, philosopher and humorist Prentice Mulford (1834-1891), left early to go mine in California. He wrote about the effects of the Gold Rush back home, and the dashed marriage prospects for women left behind. Eventually Mulford befriended Mark Twain and Bret Harte, and became a San Francisco “Bohemian”. He lived in an old whaleboat that cruised San Francisco Bay before coming back east to live in New York City, and died on the way back to Sag Harbor, presumably coming to visit his sisters who ran a small school here. Forty years later, another Sag Harbor native, the poet George Sterling, was remaindered by his family to California to live with his uncle Frank C. Havens, and he too became a Bohemian and eventually poet laureate of San Francisco.

San Francisco Bohemians in the Bohemian Grove

A '49er Panning for Gold

Prentice Mulford of Sag Harbor

Gold Rush Ad

San Francisco Bay full of Whaling Ships

The Astronomer of Sag Harbor

Ephraim Niles Byram (1809-1881) grew up in Sag Harbor during the height of the whaling industry. Mostly self educated, he was a voracious reader and accumulated one of the town's largest libraries. He wrote and bound his own books as well as consistently maintaining a bookbinding business throughout his entire life. Through interaction with the captains and crews of the whaling ships in Sag Harbor's international port, he became interested in problems of navigation and began repairing navigational instruments which included making his own tools. He became an expert in compasses, telescopes and other ship's gear. At 26, he won a gold medal from the American Institute for building a Universal Planetarium (an orrery) which he took on tour, giving lectures on astronomy and the solar system using a magic lantern, an early type of projector.

To us, a tower clock seems like an expensive adornment. During Byram's time owning your own time piece was still a luxury. If you were well enough off to own a clock it was more likely to be a case clock for your home rather than one that you carried on your person. The common man still looked to town clocks for the correct time of day. Byram was asked to construct a clock for the Methodist Church’s steeple, and in doing so became Long Island’s first and only known tower clock maker.

Byram's second tower clock was for the Presbyterian Church in Sag Harbor in 1845. They found that its tall spyglass-like design swayed in the wind, throwing the clock's pendulum out of beat. Unable to stabilize the clock in order for it to keep accurate time, Byram had it moved, which saved it, since the Whaler's church steeple was, like the Methodist Church’s, lost in the 1938 hurricane. The clock was moved to the East Hampton Presbyterian Church where it kept good time until it was gutted and electrified in 1969. New York City Hall and West Point Academy are two other well known Byram accomplishments.

One Byram clock that survived and that we can visit at the John Jermain Memorial Library is a tall case clock made for his own home in 1869. It was donated to the Library in 1943 by Ephraim Byram's daughter Loretta Sophia.

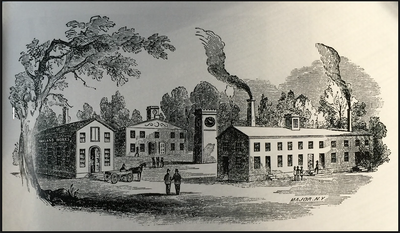

In 1850 Byram formed a partnership with John Sherry and built a brass foundry and clock factory on Byram property. An ad in Scientific American, Vol. 8, No. 16 of 1853, advertises “clocks for Churches Public Buildings etc”, in plain and jeweled movements of unequalled elegance, sold with warranties, and is endorsed by Scientific American: "At the Oakland Works of Sherry and Byram there are made some of the finest clocks in the world”. A tower was constructed at the Oakland Works to be used for Byram's astrological observations. The 1854 map here above shows the location of the Oakland works, cemetery and Byram property.

We thank artist Gail Gallagher for her extensive and excellent research on Bryam. This stop is entirely thanks to her, and more can be seen on her website.

Byram and his Orrery in the Whaling Museum

Book-Binding Ad

Map and Detail of Clock

Ad for Byram's Clocks

Horse Tied Outside his House

Byram and his Orrery in the Whaling Museum

Mulberry Mania: The Industry That Never Happened

Like the Tulip Mania in Holland that occurred at the peak of its wealth in the 1630s, the opening of the east by whaling vessels in the early 1800s led to a little-known mania that affected northeast America: our own Mulberry Mania. Companies in New England were successfully manufacturing silk, and in the 1830s there was wild speculation that a fortune could be made in silk by buying supposedly hardier mulberry trees (Morus alba multicaulis; see "Remarkable Trees of Sag Harbor") and raising silk worms. The market, however, crashed by the fall of 1839. In 1835 the trees of one Samuel Whitmarsh, a great proponent of the trade from Florence, Massachusetts, were selling at 10 cents a tree. The Massachusetts government even got into the act, offering a bounty to plant mulberry trees. After advertising and promoting them as having rapid growth and huge leaves, and promising abundant fortunes, a single tree was selling for nearly a dollar by 1838, quite an expense at the time. Trees were bought and sold just to make a profit. Farmers in New England prepared soil, tore out previous crops, and planted, but after the price of the trees crashed, many speculators went bankrupt. Subsequent winters were hard, a blight ensued, trees died, and the promised boom utterly collapsed. Silk factories, like that pictured in Manchester, CT, continued apace until the 1930s but without the successful breeding of silkworms here.

In Sag Harbor, our own astronomer/entrepreneur Ephraim Byram jumped on the craze, helped by his father Eliab and his brother Henry, an agricultural scientist. Byram put regular ads in the Sag Harbor Corrector for the sale of Mulberry trees. One of such trees remains, and can still be seen on the south side of the Hannibal French house at 186 Main Street. It’s a beautiful weeping variety and is in a protected spot, since it’s obviously survived other harsh winters.

Fahys’ Watchcase Factory

The Great Fire of 1877 (see Fire & Water: Great Disasters of Sag Harbor) changed the face and fortunes of Sag Harbor. Already in decline, when this devastating fire struck on February 18th it swept the wharves and business section of the Village, destroying 31 buildings, including the music hall, Nassau House Hotel, the Flour mill (which became the Sag Harbor Grain Company and later Grumman, where parts for the Lunar Landing Module were produced), residences on Rysam Street, and the remaining whaling warehouses.

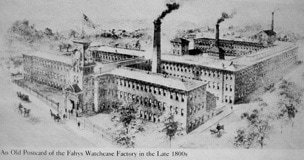

This fire was followed in 1879 by the Cotton Mill mysteriously burning, which made room for French immigrant and watchcase manufacturer Joseph Fahys to relocate his factory here from New Jersey in 1881. Fahys’ offices were in New York City, and the company not only manufactured watch cases but was one of the largest producers of silverware in the United States, becoming director of the Alvin Manufacturing Company as well. By 1886, Fahys, his partner Henry Francis Cook, and his son Ernest were the selling agents of Fahys Watch Case, Brooklyn Watch Case, and the Alvin Manufacturing Companies.

The watch case factory building is “Gradgrind" architecture, an name inspired by an inflexible, dictatorial Dickens character, and as described by Wilfrid Sheed in Sag Harbor Is: A Literary Celebration, it can fairly be described as “one of those epic anomalies that help to define a landscape by clashing with it”. It sported a social hall with billiards room and card tables, and a library. Fahys hired more than Hungarian, Italian and Polish workers, many of whom were expert engravers. Elite tool makers were paid well, but the “piecemeal” workers, literally paid by the piece, fared worse in wages. The factory led to a housing boom between 1885 and 1915, with approximately 80 small factory workers’ houses being build in Sag Harbor.

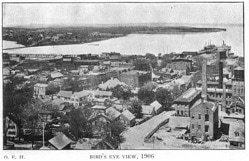

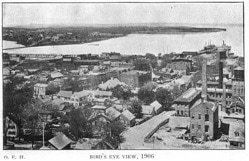

At its lowest ebb in the mid-1870s, Sag Harbor’s population had dropped to slightly over 2,000. In 1907, the Brooklyn Eagle observed that “Sag Harbor has awakened from its moribund condition that followed the decline of the whaling industry and become a bustling manufacturing village of from 4,500 to 5,000 population, but not as important relatively as fifty years ago.”

Fahys' factory was the Village’s employment mainstay thereafter until it was closed during the Great Depression, in 1931.

Postcard of Factory in Late 1880s †

Fahys Watchcase Factory †

Examples of Fahys Watch Cases *

Bird’s Eye View from 1906 †

The Alvin Silver Company

From 1911 till January 1, 1925, the Alvin Silver Company was the Village's largest employer besides the Fahys Watchcase Factory, and its enormous building housed the village's Post Office. Alvin Silver Manufacturing was originally headquartered in Irvington, New Jersey in 1886, and then was moved to Sag Harbor. The company was purchased by Joseph Fahys in 1897.

American manufacturers quickly became prolific purveyors after the discovery of silver reserves in mines in Nevada. The Alvin Silver Company was in an enormous building right on Main Street not far from the Watchcase Factory, just south of Washington St, and produced fine flatware and hollowware. Many of its patterns produced here were historical, and its dies were purchased in 1928 by the Gorham Company of Providence, RI. The Alvin Silver building was gutted and lost in the New Year’s Day fire of 1925, and is depicted in a large mural in the Firemen’s Museum at the corner Church and Sage Streets, commemorating the courage of the firefighters in that horrible conflagration. In spite of the bitter cold the day of the fire, it was so hot that window in buildings across Main Street cracked from the heat.

Alvin Silver flatware and hollowware (“Correct for Every Occasion”, as per the advertisement here) is still very desirable for collection, and you’ll see a beautiful spoon (on temporary loan at the Sag Harbor Historical Society) commemorating the Old Whalers’ Church, complete with still-extant steeple, in an accompanying photo.

Before and After Fire of 1925 †

Ad for Alvin Silver *

Alvin Silver Spoon with Old Whalers’ Spire †

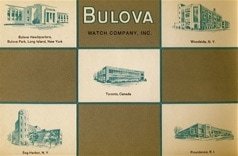

Bulova Watchcase Factory

As noted, Fahys' factory was the Village’s employment mainstay until 1931. In 1936 the Village leased the second floor to a subsidiary of the Bulova Watch Company, a likely successor, and in 1937 citizens formed a committee to raise money for renovations and new machinery. Production then increased to around 30,000 watchcases per week, at which point Bulova took over the whole building. Bulova’s headquarters was in Woodside, Queens, and it had manufacturing facilities in Sag Harbor, Toronto, and Providence, R.I.

After WWII, people routinely graduated from high school to then be employed by Bulova, or the other manufacturing interests in town, which included Rowe Industries, makers of small electric motors for toys and toothbrushes, later taken over by Sag Harbor Industries which still exists today, and Grumman, which produced parts for the Lunar Landing Module and was located at the wharf. Piecemeal labor, as had existed when it was Fahys’, could be arduous. Safeguards were put in place by OSHA laws in 1971 but the giant presses that were used without them took many digits of careless or overworked employees. Toxic cleansing agents were used in the “coloring department” and many workers succumbed to cancer. The courtyard was the dumping ground for all things chemical. Rusted-out 50 gallon drums that once held chemicals were strewn about for years; old-timers used to warn newcomers not to smoke cigarettes there.

Bulova lost valuable government contracts when retired Joint Chiefs of Staff General Omar Bradley stepped down as chairman of the Bulova Board in 1973, losing many valuable government contracts. The Sag Harbor factory produced its last watch in 1975.

After being abandoned, the contamination at Bulova was eventually cleaned up and the building now houses luxury condominiums. Kraft Foods, which bought Sag Harbor Industries, also had to undertake a Superfund cleanup at their site on the Bridgehampton/Sag Harbor Turnpike.

Bulova Factory Workers †

Bulova Renovated Today *

Academy Award Watch *

Ad for Bulova, with Sag Harbor at Lower Left *

Sag Harbor: Mecca for Writers

Ever since James Fenimore Cooper (1759-1851), America’s “first authentic American author”, came here to write, Sag Harbor has been a magnet for literary creativity. David Hand, a Sag Harbor resident, is thought to have been the inspiration for his protagonist in the novel of the same name, Natty Bumppo. Lyman Beecher (1775-1863), father of Harriet Beecher Stowe, penned sermons and preached here, and Julian Hawthorne, the “golden boy” of his family and son of father Nathaniel Hawthorne, lived on Main St. He was so successful and prolific that he is thought to have been the first American author to have earned his living from writing.

Nathan Cuffee (1854-1912) grew up in the Eastville section of Sag Harbor and co-authored a novel with Lydia Jocelyn called Lords of the Soil: a Romance Among Early English Settlers, making him the first published native American on Long Island. Olivia Ward Bush-Banks (1869-1944), of African American and Native American descent, was born here and became a dramatist, essayist, editor and poet, developing the “Bush-Banks School of Expression” in Chicago and returning often to meet with Montauketts. William Mulvihill (1923-2004) spent a good deal of his time here on Glover Street and was, besides being an environmentalist who greatly affected conservation here, an author, screenwriter, and essayist. He also wrote a still-available book called South Fork Place Names: Some Informal Long Island History.

More contemporary authors include John Steinbeck (1902-1968), who became a beloved local, and was inspired to write Travels with Charley here. Lady Caroline Blackwood (1931-1996), praised for her acerbic wit and shortlisted for the Booker Prize, spent the last part of her life here, and Nelson Algren (1909-1981) spent the last two years of his life here, developing a close relationship with Canio Pavone of Canio’s Bookstore. He enjoyed a long-awaited acknowledgment during those last two years in the form of his admission to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Langston Hughes (1902-1967), poet and leader of the Harlem Renaissance, visited frequently. Betty Friedan (1921-2006), galvanizing author of The Feminine Mystique, summered in Sag Harbor. Playwrights Lanford Wilson (1937-2011), Spalding Gray (1941-2004), and Jon Robin Baitz (1961–) all lived here, as well as Annselm Morpurgo (1934 –), head of the Savant Garde Institute in New York who penned the phrase “Come out of the closet”. Thomas Harris (1940 –) created Hannibal Lecter, his famous villain, in Sag Harbor, in an apartment on Main St. Colson Whitehead (1969 –) summered here throughout his childhood, which fact led to his novel Sag Harbor, and of course the great E.L. Doctorow, recently and sadly deceased, was a longtime resident.

Literary Sag Harbor, another tour we present, has much more information on all these writers.

Betty Friedan *

Colson Whitehead *

John Steinbeck *

Nathan Cuffee Courtesy Eastville Community Historical Society

Cooper’s "Last of the Mohicans" *

Sag Harbor in the Present

Much of Sag Harbor’s wealth is recently measured by its increasing success in providing secondary homes for wealthy residents of urban areas, but its real wealth, as these Walking Tours show, clearly resides in its rich history and community. Schools are superior, culture is alive and well, theater and art abounds, and you may want to visit the Sag Harbor Cultural District Tour for more information.

Main Street sports some of the most authentic and beloved places in the Hamptons, like the Sag Harbor Variety Store, a real “Five and Dime”, and our beloved Sag Harbor Cinema (now, sadly, the victim of a devastating fire on December 16, 2016, that destroyed the front portion of the Cinema. It has yet to be rebuilt, but we are hoping to reinstate it). The Sag Harbor Chamber of Commerce actively engages the community, and sponsors events like Harborfest, a harvest celebration held in September, and Harborfrost, a terrific fireworks and ice-carving weekend in the winter. See their website and our Sag Harbor Cultural District Walking Tour for more information!

Sag Harbor Cinema *

John Jermain Library Being Renovated §

Harborfrost §

Sag Harbor Variety Store =

Sag Harbor Whaling Museum §

“An Open Door Since 1844”: Christine Grimbol

Christine Bech Rannie Grimbol (1945-2000) was born in Bristol, PA, to a mother who died in childbirth and whose father and three-year-old brother drowned when she was only 10 months old.

Going to live with an aunt, she then suffered years of sexual abuse from her uncle. When her aunt died, she was sent to another relative, finally finding solace and salvation in the church and the choir. She received a degree in music from the Westminster Choir College, and a divinity degree from Princeton Theological Seminary, where she met William Grimbol. While serving at a church in Milwaukee where she ministered to battered women and fought racism in schools, she and Grimbol, also a minister, married. The Grimbols then came to Sag Harbor in the mid-1980s to serve the small, aging congregation at the First Presbyterian (Old Whalers’) Church, a National Historic Landmark.

Like many people who arrive in Sag Harbor, Chris Grimbol thought of it as her first real home and hometown, and set out to befriend the community. She hung out with the tough-talking fishermen at the delis, wrote sermons while chatting with patrons at the Paradise Diner, and very deliberately set out to meet the youth of Sag Harbor. When Chris and Bill were students at Princeton, classmates had nicknamed her “Easter” and him “Black Friday" because of her more upbeat view of her faith, which he claimed eventually rubbed off on him. She was intent on giving the kids of Sag Harbor purpose and hope, and Bill Grimbol remembered her going up to a group of hardened kids shortly after they'd arrived, saying “The youth group meets on Sunday at 6:30pm. Where do you live? I’ll pick you up.” He added, “It was like the Charles Manson boys’

chorus. She just went and got everybody."

No one, regardless of race or sexual orientation, was off her radar, and she was fearless about sharing her own personal story. As Annette Hinkle aptly put it, she saw the church as a hospital for sinners, not a sanctuary for saints.

Esther Ricker, who’d been part of the church governing committee that hired Ms. Grimbol, said that in 1957, when she first joined the church, if there were 25 people there on a given Sunday that was a lot. Before Chris Grimbol’s death, almost 600 people packed the church for Easter Sunday.

Grimbol coined the motto of the church in 1994, at its sesquicentennial, "An open door since 1844". She then added, “And we’re not about to close it now”.

Besides her church and hospice work, Ms. Grimbol helped found the East End AIDS Wellness Project and worked for feminist causes, supporting the pro-choice movement.

Complications from gastric bypass surgery led to her death in April, 2000, at the age of 54. Red roses and black ribbons were strewn on the steps of the church in her honor, and 1,000 mourners were present for her funeral.

Christine Grimbol

First Presbyterian (Old Whalers”) Church‡

Grimbol Playing Guitar ‖

Contemporary Hero Linda Gronlund

Linda Gronlund was born September 13, 1954 and died, significantly, on September 11, 2001. Her mother, Doris, owned the Sagalund Store clothing store until 1997. Linda graduated from Pierson High School in 1972, went to Southampton College, and earned a law degree from American University in 1983.

A lover of nature and an accomplished sailor, scuba diver and brown belt in karate, Linda was also an avid race car enthusiast and at the age of 12 restored a car with her father. She worked as a flagger at the Bridgehampton Race Track and was a member of the Sports Car Club of America.

She eventually landed her dream job, as Manager of Environmental Compliance for BMW North America.

On September 11, 2001, she and her boyfriend Joe DeLuca boarded UA Flight 93 from Newark bound for San Francisco. They were on their way to travel to wine country to celebrate her upcoming 47th birthday.

Linda was in seat 2A, Joe next to her in 2B, sitting right behind one of the highjackers. As the highjacking took place, passengers called families and learned about the other attacks. Linda called her sister beloved Elsa, telling her where her will was, and also told her family how much she loved them.

Doris Gronlund is sure that Linda would have been among the group of passengers who fought back and kept the plane from reaching its target, when it crashed into a field in Shanksvile, PA. As she said in an interview in the Sag Harbor Express, "I always want people to remember Flight 93 because they were unique. They did not choose to let that particular plane become another missile so the next target, the White House or the Capital would be destroyed. What a different picture we would have of that day if that had happened."

BMW has set up a scholarship in her memory, awarded annually to a female engineering student at MIT, and Barcelona Neck Preserve was renamed the Linda Gronlund Memorial Nature Preserve on September 11, 2004.

Ed. note: Special thanks to Annette Hinkle for her research on Linda Gronlund, to Elsa Gronlund for permission to reproduce two of the photographs seen here, and to Doris Gronlund, who has remained an inspiration for those who have suffered loss from the 9-11 attacks.

Linda Gronlund†

Flight 93 Dedication (Photo: Chuck Wagner)

Linda and sister Elsa†