CORNICES AND PILASTERS:

SAG HARBOR ARCHITECTURE

Umbrella House §

Annie Cooper Boyd House

1693 House †

Prime House ‡

Sag Harbor, for its small acreage, sports an outsize abundance of architectural styles. If you’re like us, you may find distinguishing between Georgian, Federal, Queen Anne, Colonial and other building types here rather overwhelming. As you can imagine, there is overlapping of style and ornamentation, but this tour is designed to give clear examples most of our major architectural representations. We’ll focus on Main Street, with just a few detours, to make this manageable, and afterwards we guarantee you’ll feel more at home on this topic!

You should also know that we are a National Register Historic District, of which we are rightfully proud. This tour is made possible thanks to Jean Held and the Sag Harbor Historical Society, who kindly shared their re-publication of Robert Pine’s exceptional 1973 book Sag Harbor: Past, Present and Future, originally prepared for the Sag Harbor Historic Preservation Commission. Almost all information in this tour comes from that publication and, thankfully, most of his references are still standing.

An important note: Although we focus on the classic architecture for which the Village is best known, we must mention the wealth of wonderful vernacular architecture here that has been manifested in much workforce housing, built after Sag Harbor reinvented itself after the collapse of the whaling industry and its many devastating fires. The still-extant Sears and Roebuck mail-order houses and the inventiveness in many of these vernacular styles is fascinating in itself, and much of Sag Harbor’s cultural history can be found here as well. We hope you’ll continue to explore the village in its architectural entirety beyond the examples cited here.

COLONIAL STYLE & HALF HOUSES

(C.1750-1790)

Let's begin with a great example of a half house, the Prime House (c.1795) found at Madison and Sage St. It is also one of the oldest houses in the village, and another example is the 1693 House, at 62 Union St, built in Sagaponack and moved five times! The typical domestic home which emerged in America by way of English architectural handbooks was a home five bays wide—here bays refers to the windows which divide a building–with a center hall plan, but most people could not afford a house that large; outside of a few major centers like Boston and New York, communities were still forming and settling. And so the half house type became popular, usually a three bay house with its door at one side.

The half house was the dominant domestic form of city and country dwellings until the books of A. J. Downing popularized a less formal spatial arrangement in the 1950’s. An excellent example of a Colonial house is the Umbrella House at 89 Division St, which was used by the British in the Revolutionary War, and another is the Annie Cooper Boyd House at 174 Main St, which houses the Sag Harbor Historical Society.

Half houses usually have pitched roofs, and are one and a half stories. Chimneys are within the walls of the house, and windows were originally casement-style. Doors were simple, with or without small transoms (a window just above a door), but originally without sidelights (windows on either side of the door) and lead tracery (the supporting decorative metalwork within the window itself). You'll see a lot of beautiful transoms and sidelights throughout the village. Work on these half houses was all done by hand.

Sybil Douglas house†

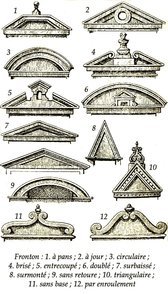

Pediment forms from an old French architectural guide*

A Pilaster, which may be on the inside or outside a house*

Example of a Cornice (in this case on the Hannibal French house at 186 Main Street ‡

GEORGIAN (NATIONALLY C.1720-1780)

Sag Harbor has a few houses with fine Georgian characteristics but all post-date the technical Georgian period, ranging from 1800-1835. This style was diffused through English handbooks containing drawings of individual elements like pilasters (pilasters look like columns but are ornamental rather than structural, often attached to a wall or door frame), pediments (the finishing caps of columns and pilasters), cornices (horizontal decorative molding that crowns a whole building or a furniture element), and interior staircases. Its architecture is typified by pitched, gambrel, or hipped roofs, and cornices often feature bold modillions (brackets underneath a cornice. Brackets can be structural or merely decorative). A semicircular fanlight first appeared over doors around 1760. The elliptical fan was not used till 1793, and is a Federal form. An enclosed pediment supported on columns or pilasters was a typical elaboration of the door frame.

Sag Harbor’s prosperity began after it became a Port of Entry in 1789, and it was not until then that such high-style houses would be typically found. The Sybil Douglas house at 189 Main St. pictured here is a prime example of Georgian style.

Jared Wade House †

Van Scoy House †

Custom House at 198 Main †

Beebee House on Suffolk and Jefferson St ‡

FEDERAL STYLE

(C. 1780 - 1830)

American architecture came into its own fashionable self with the Federal period. America’s independence was a true factor in its emergence; Federal architecture has symbolic, Romantic qualities, and they usurped the popularity of the preceding Georgian mode and its inspiration, the Age of Reason. It had its roots in Europe, however. Moral appropriateness and simplicity were its ideals, and it coincided with increasing travel to Pompeii and a concomitant appreciation of classicism, leading to what Robert Pine described as “delicate, confined classical ornament”, typified by Englishman Robert Adam’s architecture.

Thomas Jefferson’s Roman-inspired classicism influenced the entire east coast, and is an example of what is known as “polite” architecture, in which stylistic or romantic features are incorporated by an architect for affectation.

Federal architecture’s characteristics include one-and-a-half to two stories, and a doorway with often rather elaborate transoms and sidelights. In Sag Harbor one finds “mantelpiece” door enframements, consisting of side pilasters, often reeded or sometimes molded, that form a full entablature that hearken to interior mantels. Leading of windows is often beautifully delicate. The Jared Wade house, at Union and Madison St, is a prime example of this form. Roofs are pitched, and Sag Harbor has a number of gambrel-roofed Federal houses, especially associated with the work of Benjamin Glover, like the Van Scoy house at Main and Jefferson. Shingling was often used on three sides, with clapboard on the front.

L’Hommedieu House †

Whaling Museum †

Stanton House †

GREEK REVIVAL

(C. 1825-1845)

In the case of this classic revival, American architects and builders took the initiative before their European counterparts, and exploited its potential to a greater degree. Greek Revival remains one of the most significant manifestations of colonial America’s national spirit and success. The publication of a 1762 book by James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The Antiquities of Athens, inspired it. The architects who evinced the style, Latrobe, Mills, Strickland and Minard Lafever, the latter so visibly in evidence in Sag Harbor, were its leaders. Popular handbooks disseminated the style. Our most impressive examples of it are the First Presbyterian (Old Whalers’) Church (1844) in the Egyptian Revival style, 44 Union St, and the Benjamin Huntting house (now the Sag Harbor Whaling and Historical Museum) at 200 Main St, both by Lafever. Chronologically, this style coincided with the greatest boom of wealth Sag Harbor had ever known, from the whaling industry. Newly wealthy whaling captains wanted to show off, and a handsome and important house was the most ostentatious way to do this. The style was so firmly rooted here that various aspects of it were continued in examples of Victorian houses much later, like the Greek Revival doorway form.

Water-powered circular saws were introduced into carpentry and housebuilding at about this time, and nail-making machines had been invented, so production challenges were decreased. Greek Revival roofs tend to be pitched gable. The majority of houses of this period were basically traditional in form, but enriched with Greek Revival ornamentation. There is even an urban manifestation of this style in the L’Hommedieu house, at 258 Main St, which has an elegant doorway with a recessed entrance, and whose characteristics are found on brick houses in Boston and New York. The L’Hommedieu house is brick, but clapboard is more typical. Cornices are very important, and where the facade is at the gable end, both flat and raking cornices usually exist, outlining the pediment at attic level; think of the Parthenon friezes. Doors had sidelights and leaded transoms. Pilasters were invariably Tuscan (see the L’Hommedieu house), used with cornerposts and extending from the water table (an element that deflected water from a building, often where materials transition) to the architrave (the lintel or beam that connects the columns).

Hedges House at Main and Madison ‡

Municipal Building †

The American Hotel †

249 Main St ‡

GOTHIC REVIVAL

(C.1835-1855)

The Gothic Revival offered an alternative to the Greek Revival. It appealed, once again symbolically, to a sense of the “picturesque” and the “natural”, a variant of Romantic Classicism which referenced the romantic naturalism of Jean Jacques Rousseau. In its philosophy, architecture best attained the picturesque (a preoccupation with architecture and landscape in combination with each other) in the form of the spire, as in a gothic building, like Medieval cathedrals, also imitated in university buildings like those of Oxford, famous for its spires.

Alexander Jackson Davis, an American architect, is credited as having invented the first Gothic Revival house around 1835 and it was popularized by Andrew Johnson Downing in Architecture of Country Houses, probably the most widely distributed architectural handbook in America, in 1850. The style eventually morphed into the Victorian, and it can be divided into two basic types, one round-arched and blocky, or Italianate (like the Municipal Building at 55 Main St, which even has a campanile) and the other vertical and usually pointed, or Gothic, like the example at 249 Main St. Long one-story verandas, which were a feature, came into popularity at this time. Exterior walls were always painted a neutral, “natural” or “stone” color, to blend into the surrounding nature.

If there were enough ground to landscape, its model was the so-called “natural” English garden, like those of Frederick Law Olmstead, of Central Park fame. Pine writes that these “buildings can sometimes be dated by the elaboration of eave brackets” and Gothic Revival and its extension into Victorian styles sported bracketed eaves with extended purlin (supports for roof rafters) and rafter ends, which later became elaborately scrolled, often with turned pendants. After the Civil War, brackets were often used in pairs. This is also the period in which the term “gingerbread” began to be used, and surprisingly, it comes from medieval French, the term gingimbrat referring to preserved ginger, used in spiced cakes baked into fancy shapes. It was first used in reference to English architectural ornament in the 18th Century, and can abundantly be seen in the Hedges House at 133 Main St.

Howell-Napier House ‡

Hannibal French House †

Hope House ‡

Byram House †

EARLY AND HIGH VICTORIAN ITALIANATE

(C. 1845-1875)

The Italian village was an English invention (!) of the Regency period. It was inspired by architecture found in paintings of Italian landscapes such as those by Claude Lorrain, and often punctuated by bell towers (or campaniles, in Italian) (see the Ephraim Byram house, built on Jermain Ave next to Oakland Cemetery in 1852). In Putnam’s Monthly Magazine of April, 1854, it was noted that “The Grecian taste…has…been succeeded and almost entirely superseded, both here and in England, by the revival of the Italian style.”

Early Victorian Italianate was characterized by a low, blocky mass, extended bracketed eaves, round-arched windows, shadowy porches (called “umbrages”) and square towers. In Sag Harbor Italianate houses often incorporate earlier forms such as the corner pilasters of the Greek Revival, and the paired brackets of the previous Gothic Revival style. The later years of this style were in the High Victorian era, contemporaneous with the mansard-roofed style.

Typical characteristics include two stories, several sections of roof, and extended eaves. The most advanced of these houses had double doors, often with segmental-arched tops, like the 1860 Hannibal French house at 186 Main St, one of the most elaborate in the Village. You’ll also see one of our famous Roof Walks at the top of the Howell-Napier house at 238 Main St. Many people think of roof walks as "widow's walks", but they were not intentionally built for whaling wives to look out at the sea, nor was their other popular name "captain's walk" designed for nostalgic captains to gaze at the horizon. In fact their practical function and architectural origin was to store sand in the event of a chimney fire (which was a common problem). Both houses were built at the height of the whaling industry.

Two Ruskinian Gothic Houses ‡

High Victorian Gothic House at John and Columbia ‡

HIGH VICTORIAN PERIOD: RUSKINIAN GOTHIC

(C.1865-1885)

The Gothic Revival was revitalized and reformed through the writings of English critic John Ruskin. Both of his wildly popular books, Seven Lamps of Architecture and Stones of Venice, were influential here. In later Victorian styles “reality” overtook “beauty” as a goal, but nature was still the source of these qualities, and nature seen as an upward-tending model, as in Gothic Medieval architecture, was still used.

In America, High Victorian Gothic produced rich, high, densely massed buildings with steeply pitched roofs or mansard variants, often with gables, bays, and turrets. Various colors and textures were used, and this produced a rich play of light and shade. The more sophisticated, or turreted, Victorian Gothic idiom was transformed into the late Victorian picturesque or Queen Anne Style. A good example of a Ruskinian Gothic house and can be found at 265 Main St., and another more modest example is at 299 Main. A High Victorian can be seen a little further afield, at the corner of John and Columbia St. and is an excellent example of the form.

Queen Anne Store at 26 Madison ‡

Queen Anne Style at 22 Palmer Terrace

Howard and Main ‡

LATE VICTORIAN: QUEEN ANNE

(C. 1880-1910)

Queen Anne style was also a conscious evocation of an architectural past, but specifically concerned village architecture that was prevalent during the reign of Anne Stuart, Queen of England from 1702-04. Richard Norman Shaw was its great proponent in England, hailing from the 1870s, and it manifested about ten years later here.

It was typified by the presence of turrets, ornamental brick chimneys, and asymmetrically placed porches with turned rails and spindle work. The “Queen Anne Window” combined large plate glass panes with small mullioned panes, with or without stained glass. This style also employed rich textural variety, combining masonry and wood, often with stone and brick at ground level, and diagonally boarded or shingled walls above. You'll see a superb example at 27 Palmer Terrace and a good example of Queen Anne style at the southwest corner of Main and Howard Streets.

A Shingle Style house at 32 Palmer Terrace‡

Colonial Revival house at 56 High Street

SHINGLE STYLE AND COLONIAL STYLE

(C. 1880-1960)

The American Centennial celebration of 1876, in Philadelphia, provided an arena for the display of architectural styles popular at the time. Much of it was in the late Victorian Gothic style. But in a spirit of historical appreciation, interest reawakened in older styles and led to the rise of the Georgian Revival style, called Colonial Revival here in the States.

Shingle Style was modern, with no historical allusions. One of its major proponents was the firm of McKim, Mead and White, as in the famous architect Stanford White. Colonial Revival houses of around 1900 are close to the Shingle Style, often with porches that are occasionally included under the sweep of the eaves, and enclosed with round arched “loggias”. As Robert Pine puts it, “The late 19th century was an era which had absolute faith in the idea of the front porch”. We have a true example of Shingle Style at 32 Palmer Terrace, and a Colonial Revival, with modifications, a little further away at 56 High St.

As you wander Sag Harbor, you’ll find many recombinations of building styles here, and we hope you’ll enjoy the wonderfully preserved character of our unique village.