WOMEN OF SAG HARBOR

Women of Sag Harbor invites you to time-travel from the 1800s to the present, watching the changing roles of women in our society, and celebrating the inventiveness, courage, and brilliance of the women here represented. In small and large towns in America, it is often women who are the principal keepers of their shared past and the preservers of their history, and Sag Harbor is no exception. From the Ladies’ Village Improvement Societies to the Historical Societies, they know how to propel culture forward and respect the past, and it is to them that this tour is dedicated.

Our specific thanks goes to Annette Hinkle and Anthony Garro, who spearheaded the formation of this tour, and without whose guidance it would not be possible. Sharing and compiling information with them as well as the Sag Harbor Historical Society and the John Jermain Memorial Library has been an education and a joy.

.

(It’s Only) Ms. Watkins’ Business: Being a Woman in the 1800s

Sarah Howell (1814-1891) lost her former whaling husband George on his way home from the California Gold Rush in the 1840s, after he contracted cholera. She and her young son Henry were saddled with debts, some of which could not be proven, but which she was intent on paying, being a proud and honest women. After his death, their dream house at 68 Bay Street and its possessions were in jeopardy, and in 1851 its contents were piled into four carts, along with George’s coopering tools, to be sold at auction. Sarah was only allowed to keep minimal goods: the Bible, a few books, two beds and bedding, clothes. Although Sarah had moved in with her mother, accepting tenants for the house to stay afloat, she eventually had to sell it. Sarah worked as a seamstress and Henry joined the Navy when the Civil War started. He was killed when the magazine on his gunboat accidentally exploded when he was 21 years old.

Sarah received a modest pension from the government for the death of her son and began traveling, later marrying a man named Gideon Nicholl (who also predeceased her). She returned to Sag Harbor and died in 1891 at age 77, buried near George and Henry in the Howell plot near the Broken Mast Monument in Oakland Cemetery.

Sarah and George’s house at 68 Bay Street was for some time rented by a Mary A. Watkins, who was reported being there in the very thorough Census of 1850. In it, Mary Watkins was listed as the head of the household, with her six children, as well as Edmund Crunk, 12 years old, and 15 young women aged between 9 and 35. Most of the women came from out of state, and no occupations were listed for any residents of the house. There was a cooper’s shop next door, and it had been described by Oliver Wade, a Sag Harbor native, as a most lively place, full of jolly men, and where “dazed and drunken sailors” would have a rest on the grass at the nearby pond after their debauchery. It should be noted that these sailors, come back from whaling, had good reason to cut loose when back on land. They could be away for years at a time, were often poorly paid and mistreated, suffered diseases specific to life on a ship in those times, and were subject to extreme danger. It should also be noted that for women of the period, there was very little choice in how to keep themselves together financially if something happened to the men on which they depended.

Not long after the 1850 census, Mrs. Watkins stopped renting the house, and disappeared without a trace. It is generally agreed that the house had served as one of Sag Harbor’s notorious brothels, servicing the sailors and whalers who gave it its gritty reputation. This reputation was described by no other than the “pagan" Queequeg in Herman Melville's Moby-Dick, when he said, "But, alas! the practices of whalemen soon convinced him that even Christians could be both miserable and wicked; infinitely more so, than all his father's heathens. Arrived at last in old Sag Harbor; and seeing what the sailors did there; and then going on to Nantucket, and seeing how they spent their wages in that place also, poor Queequeg gave it up for lost. Thought he, it's a wicked world in all meridians; I'll die a pagan." (Chapter 12, Moby-Dick, or The Whale, published in 1851)

The Dangers of Whaling

Sperm Oil Manufacturing Label

A Sailors’ Brothel in the 1800s

68 Bay St

.

Mrs Russell Sage vs. the Ponies

In 1874, what is now Mashashimuet Park was the Hamptons Driving Park and Fair, and by 1879 a half-mile oval track was built for carriage team races, trotting, and walking races. You can see the festive atmosphere in the old photo shown here, and it must have been quite a draw. The park’s popularity showed in its new name: Sag Harbor, Hampton and Shelter Island Park and Fair Grounds. It even expanded with an exhibition building built for judging produce, poultry, flowers and baked goods, although that building was destroyed by one of Sag Harbor’s many fires in 1890.

In 1893 the Great Bicycle Tournament attracted over 1,000 spectators, but sadly, by 1900 the park grounds began to deteriorate.

Enter Mrs. Olivia Slocum Sage (1828-1918). Olivia Slocum’s father had gone bankrupt after developing businesses along the Erie Canal, and ever after, financial security was of paramount importance to her. At the time of her marriage, an expressed interest on the part of women in the stock market or business generally was deemed unseemly. Her inherited fortune was from her husband, Russell Sage, who made a killing in the unregulated stock market.

Mrs. Russell Sage had great affection for Sag Harbor, the childhood home of her adored mother, and purchased the Huntting House, now the Sag Harbor Whaling and Historical Museum, after Sage's death in 1906, spending her summers there between 1908 and 1912. Besides starting the Russell Sage College, a vocational school for women that taught teaching, nursing, and other practical occupations, Mrs. Sage was an ardent philanthropist, and in Sag Harbor particularly sought to help the many poor immigrants employed at Fahys Watchcase Factory. In 1908 she bought and decided to refit the Sag Harbor Park and Fair Grounds with “scientifically designed” equipment and amenities, hoping to convert it from its vulgar amusements to those more uplifting (an irony, given the fact that her wealth had come, in a sense, from her late husband’s gambling on the stock market). There were established in the park, for instance, 114 plots for children’s gardens, and weekly band concerts were held. In 1910 she also purchased the lands surrounding Otter Pond to add to the Park property, and moved 13 houses off the land to give to needy families. Mrs. Sage also underwrote edifying activities like lectures and folk-dancing for the Atheneum Theater (see Anita Miles Anderson).

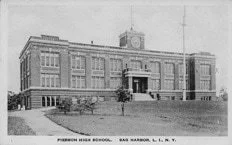

Pierson High School was another project of Mrs. Sage’s, constructed at the same time, and its name commemorated her ancestor Abraham Pierson, first rector of Yale University in 1702. Finally, she was principal benefactor of a new domed building which became the John Jermain Memorial Library, named for a local successful merchant who was her grandfather.

Mrs. Sage’s generosity was not entirely appreciated by the community, and Mrs. Sage abandoned her manse in anger in 1912 after discovering that contractors for Pierson High School had cheated her by using cheap construction materials rather than those she had paid for. There were also reports of vandalism against fixtures in her park. She did allow William Wallace Tooker, self-trained ethnologist and “Algonkinist”, to rename the park in 1908 with the Algonquin name Mashashimuet, meaning “Place of the Great Springs”, the name it still enjoys today.

Mrs Russell Sage

the Whaling Museum‡

Pierson High*

The JJML Library*

The Park*

The Old Racetrack*

Annie Cooper Boyd, "As Good as a Boy"

Annie Burnham Cooper Boyd (1864-1941), daughter and granddaughter of boatbuilders in Sag Harbor in its whaling heyday, lived at a time when the boatbuilding industry was flagging. She was the youngest of eleven children, and was indulged by her parents, especially her warm and engaging father. Her father worked as a boatbuilder in the whaling industry’s heyday and later partnered with his brother Gilbert as a dry-goods merchant. Annie grew up in a fine house on Main Street and became a person that loved nature, having a deep sense of the place Sag Harbor and the landscape around it represented.

As a child, Annie was a tomboy, a girl who was “as good as a boy” as described in her own diary, on horseback or out on the water, where she frequently painted the place she loved so well (even while on horseback!). Her love of painting only deepened after marrying John Boyd in 1895, although she changed her abbreviated signature to ACB from ABC. In 1894, after her marriage, she was bequeathed the old cottage of 1796 at 174 Main Street, which was set back next to the family’s home. At the time of it being given to her, Annie and her husband lived in Park Slope, but eventually lived there full time. Annie later directed its conversion to a house with dormers and a welcoming front porch, intent on letting nature in, and adding a bathroom and electricity in the 1930s. It’s fitting that it later became the home of the Sag Harbor Historical Society,thanks to Annie's daughter Nancy Boyd Willey’s, who inherited it and then gave it to the Society. It is still known as the Annie Cooper Boyd House.

Annie studied at William Merritt Chase’s Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art in Southampton and was a prolific artist. Although not an aggressive feminist per se, her life bespoke independence and she wrote that she “hates dependence and shall be glad when women shall be as free and indepenedent as men.” She was no Sunday painter, keeping scrupulous accounts of her work and referring to it as a business. Her work chronicles the changing landscape of Sag Harbor and environs.

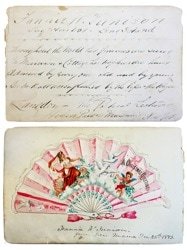

Annie named her cottage “Anchor to Windward” in 1904, referencing sailors who recognize a secure, safe mooring for their crafts by throwing their anchors into the wind. The house became a tea room (the Herald House Tea Room) when Annie needed additional funds during the Depression, and she served tea herself, selling her artwork and handmade holiday cards to guests.

Annie’s diaries provide a touching glimpse into life in Sag Harbor from 1880-1935, when the village was in decline but was of course still beloved, especially by one who had such a poignant grasp of its unique charm as she. The Sag Harbor Historical Society continues to uphold her legacy and intent, recently constructing the William H. Cooper Whaleboat Shop on its property, which has old shipbuilding tools and fascinating remnants of the whaling industry in honor of Annie’s father and grandfather.

Ed. note: Special thanks are due to Jean Held of the Sag Harbor Historical Society for guidance on this entry.

Annie Cooper Boyd

Childhood home

Paintings in the Annie Cooper Boyd House (pictured in Sag Harbor Historical Society Tour)*

Annie With Friends*

Olivia Ward Bush-Banks: "Proud Reverence and Respect"

Olivia Ward Bush-Banks (1869-1944) was born on Glover Street near Main (exact address unknown). Her parents Eliza Draper and Abraham Ward were both of mixed African-American and Montaukett descent and they moved when she was an infant to Rhode Island. She returned to our area many times to attend tribal meetings around the turn of the century when Native Americans were vying for civil rights.

In 1889, she married Frank Bush. The couple had two daughters, and after Ward and Bush divorced around 1895, Ward supported her daughters and her aged Aunt Maria. She married Anthony Banks in 1916, moving to Chicago in 1918.

Bush-Banks was a dramatist, essayist, editor and poet, and her writing reflects her rich heritage. She published regularly in the journal Colored America, and served as the official historian for the Montaukett nation. She also wrote a column for the New Rochelle, New York publication, the Westchester Record-Courier. Her books include Driftwood and The Trail of Montauk (A Dramatic Sketch of Indian Life) which was intended for the stage. Her work preserved regional and ethnic dialects that would otherwise have had no written record, as well as some of the Algonquian Montauk language and folklore. After moving to Chicago, she focused her writing on the African-American experience.

She became an advocate for the “New Negro Movement”, developed her own “Bush-Banks School of Expression”, a nexus for writers, musicians, actors and artists of color, and participated in the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in the 1930s. Her friends included Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Paul Robeson, Julia Ward Howe, and W.E.B. DuBois.

Original Poems, published in 1899, was dedicated "with proud reverence and respect" to the African American race. It was comprised of only 10 poems, concluding with "Voices":

I stand upon the haunted plain

Of vanished day and year,

And ever o'er its gloomy waste

Some strange, sad voice I hear.

Some voice from out the shadowed Past;

And one I call Regret,

And one I know is Misspent Hours,

Whose memory lingers yet.

Then Failure speaks in bitter tones,

And Grief, with all its woes;

Remorse, whose deep and cruel stings

My painful thoughts disclose.

Thus do these voices speak to me,

And flit like shadows past;

My spirit falters in despair,

And tears flow thick and fast.

But when, within the wide domain

Of Future Day and Year

I stand, and o'er its sunlit Plain

A sweeter Voice I hear,

Which bids me leave the darkened Past

And crush its memory,–

I'll listen gladly, and obey

The Voice of Opportunity.

Olivia Ward Bush-Banks

Collected Works

Bush-Banks Meeting with Members of the Montaukett Tribe in 1931

Fannie Tunison, "Without a Parallel in the World"

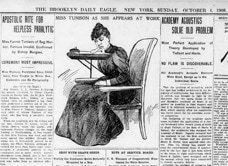

Fannie W. Tunison (1879-1944) was afflicted with infantile paralysis shortly after being born to Abraham Tunison and Fanny Coles, almost immediately losing the use of her arms and legs. Her carpenter father built special implements so that she could work, including a chair with a work bench, and she was able to paint, draw, embroider, cut out paper flowers, and sew using only her mouth & tongue, even playing the metallophone, a xylophone-like instrument struck with a mallet. She was also credited with having done pyrography (wood burning). She won first prize in "sewing and fancy articles” at the Minnesota State Fair. She eventually supported her entire family who lived at 14 Hampton St and included her mother, father and two dependent cousins, exhibiting & selling her work at fairs, and became a vaudeville attraction, a fortune teller and card reader.

Descriptions of Ms. Tunison appear in many, many publications, from America to England. For example:

WITH HER TONGUE / A Crippled Girl Sews, Embroiders and Paints With That Member

Miss Fannie W. Tunison of Sag Harbor, Long Island, is probably the most wonderful cripple in the world. Since the day of her birth her hands, feet, legs and arms have been paralyzed, but, being of a most ambitious nature and entirely unwilling that she should be only a useless burden to those around her, she has, by the most untiring and painstaking efforts, trained her tongue to perform many of the duties usually accomplished with her hands. Her case, according to the best medical authorities, is without a parallel In the world, and to those who have seen this young lady at work It hardly seems possible that she could do all that she claims.

Miss Tunison, who is about 30 years old, is In no way deformed; in fact, she Is a very good-looking young lady, bright and Intelligent, and an excellent conversationalist. She lives with her father and two cousins In a little fisherman's cottage, which was built by her grandfather, a sea-faring man and a soldier of the war of 1812. Every morning Miss Tunison, who Is an early riser, is lifted by her father into her Invalid's chair, which has a cleverly constructed work table attached to It. In this chair she remains throughout the day, held in by a strong band, which also supports her body, which is entirely powerless. In the winter her chair is placed by the front window so that she can see the people passing along the sidewalk, while in summer she Is wheeled out of doors and taken around the village. Every one in the place knows the young and cheerful Invalid.

From the time she Is lifted Into her chair In the morning until she retires at night she Is never Idle, as she is engaged In painting pretty bookmarks and blotters, embroidering doilies, mats and tidies, making attractive table covers, linen outline quilts, or quilts of craze, outline patchwork. All of this work is done with her tongue and mouth, and without the slightest assistance, as she threads her needle, knots her thread, and even uses a pair of scissors with her tongue…

In drawing she uses wax crayons, or soft lead pencils. She is fond of drawing flowers with colored wax crayons… In stringing beads she Is remarkably dexterous. She will place the needle, after it is threaded, upright In the cloth to hold It, and then with her tongue she will pick up some beads, one by one and place them on the needle. When the needle is full she will take it out of the cloth and let the beads pass down on the thread and then put the needle in place again for more. She has a metallaphone, on which she loves to play occasionally to amuse herself, and will often when she has friends in to see her show them how she uses It. She places the Instrument on the table, and, holding the mallet in her teeth, will manipulate It dexterously with her tongue.—Brooklyn Eagle, as reported in the Los Angeles Herald, 20 August, 1899

And in the New York Times, published July 27, 1902, it was reported in an article in Vaudeville and Concert Programs: “After undergoing extensive alterations, Huber’s Fourteenth Street Museum throws open its doors to the public to-morrow. For the opening week the management presents Fannie B. Tunison, the Sag Harbor woman who, deprived of the use of her arms and feet, executes by lip and mouth, specimens of painting, drawing, needlework, and sewing. Trixie, the European performing horse, will be seen here for the first time in some astonishing feats of 'horse sense’. In the theatre annex Francis Wood, novelty hoop roller; Barr and Denton, in comedy sketches; Marie Elmer, comedienne; Mae Cory, in illustrated songs, and Leo F. Welch, the funny east side Hebrew, will supply the entertainment.” It’s interesting to note the much longer description Fannie merits in this article than the other reported acts.

Fannie Tunison is buried in Oakland Cemetery. She never seems to have lost an ounce of dignity or good-humoredness in her occupations, and inspired awe in all who met her.

Fannie Tunnison ¶

Article from 1908 in the Brooklyn Eagle

Her Needleholder ¶

Christmas Card from her Mother ¶

12 Hampton Rd

Anita Miles Anderson: Burning Down the House

Anita Miles Shelton Anderson was born in 1904 in an elegant house at 20 Jefferson Street where she grew up with two cows, a horse and, architecturally notable, a coffin wall (a curved wall that could admit the maneuvering of a coffin for its display on an upstairs floor). Anita studied at the Chalif School of Dance in New York, intending to become a professional ballet dancer, but after contracting polio at the age of 20, was forced to abandon that goal. She was present when the Custom House was moved to its present location, boated to Long Beach in the summer to swim (there being no road at the time), and gave wonderful Christmas parties. She married Kenneth W. Anderson in the Old Whalers’ Church in 1932.

At the northeast corner of Sage and Church Streets, a sign designates the original site of the Sag Harbor’s first real theater. The Atheneum was very popular in the Village at the turn of the last century. It variously hosted the Masons, dances, basketball games, and even sported – no pun intended – a bowling alley in its basement.

On April 30th, 1924, the Atheneum was hosting a benefit. Anita had been studying dance in New York that winter and was asked to perform for the evening. She was accompanied by a violinist and singer, and for her performance, she had decided to do an “Oriental" dance, wearing a “bra of gold cloth, and the skirt was long black chiffon, which was banded in gold.”

“While we were practicing I said, 'Turn out the footlights when I come out to dance’. Well, they didn’t turn out the footlights, and when I came out to dance, the footlights practically took my skirt right off me… That night, the Atheneum burned down, and I never lived it down. They all said that I set the Atheneum on fire." (–from Voices of Sag Harbor: A Village Remembered, 2007, Edited by Nina Tobier)

One can only imagine the see-through effect of those footlights in 1924! Ms. Anderson died on April 7, 2005, at the age of 100.

The Atheneum was beloved and its fiery loss was mourned by Sag Harborites, who then turned to Guild Hall, in East Hampton, for their theatrical satisfaction. Now, of course, Sag Harbor is lucky to have Bay Street Theater.

Anita Anderson*

A Thanksgiving Performance at the Atheneum*

The Atheneum*

Her Family Home

Nancy Boyd Willey, Preservationist and Environmentalist

Annie Cooper Boyd’s daughter Nancy Boyd Willey (1902-1998) excelled. As a child growing up in Brooklyn, she skipped grades, was head of her class, and earned the highest academic achievements. Although living in Brooklyn, her mother Annie returned to the Sag Harbor homestead to give birth to Nancy. The family spent summers in Sag Harbor and Nancy clearly had her roots here, saving pennies to buy a canoe when she was 11 years old.

She and her good friend anthropologist Margaret Mead studied at Barnard College together, after which, in 1924, she married Malcolm Willey. The had met when he was at Columbia University getting his PhD in Sociology. He taught Sociology at the University of Minnesota while Nancy worked as a statistician, sending money back to her mother for improvements for the Annie Cooper Boyd House.

During their marriage, Nancy became more and more interested in historical preservation, as did Malcolm, who wrote articles for the Long Island Forum and the Sag Harbor Express. Nancy was President and historian for the Old Sagg-Harbour Committee since its inception, writing educational pamphlets about Sag Harbor’s history. The couple was also enthusiastic about the present. In Minneapolis in 1932, while Malcolm was an administrator at the University of Minnesota, Nancy wrote a letter to Frank Lloyd Wright, boldly asking him to design an inexpensive house for them. A lively and influential correspondence ensued between Wright and Nancy. What became a collaboration on the Willey house inspired Wright to begin a new period in his work, which is evinced in his book The Natural House, and their house came to be known as “The Willey House” or “The Garden Wall”, as the couple referred to it. The house became a pivotal point in Wright’s later career, inspiring him to make well-designed houses for “real people”.

Nancy and Malcolm divorced in 1954, Nancy moving back to New York, and then in 1965 retiring to the Annie Cooper Boyd House. Nancy had not lost touch with the village. In the late 1940s, she and friend Josephine Bassett had led a successful endeavor to save the old Custom House from demolition, having it moved to its present location on Main Street adjacent the Sag Harbor Whaling and Historical Museum, a move witnessed by many residents as an historic moment.

Two of the most important accomplishments of Nancy Boyd Willey were the establishment of the Sag Harbor Historic District and the Village’s Historic Preservation and Architectural Review Board, both meant to protect its unique and important architectural history.

The Annie Cooper Boyd House served as the founding site of the Old Sagg-Harbour Committee, as well as the Sag Harbor Conservation and Planning Alliance (CAPA). This important conservation group saved Little Northwest Creek and wetlands from development in 1974, and also preserved Barcelona Neck. Other critical successes include the establishment of Trout Pond as well the preservation of land in the Long Pond Greenbelt, an area with unique geology and fauna. Regrettably, their efforts to preserve Sag Harbor’s open space waterfront failed.

The pioneering work that Nancy Boyd Willey achieved set the precedent for the Sag Harbor Historical Society, and brought the burgeoning conservation movement of the 1960s home to Sag Harbor. Willey’s final act of preservation was the willing of her home, the Annie Cooper Boyd House, to the Sag Harbor Historical Society.

Ed. note: Our thanks to the Sag Harbor Historical Society, and especially Jean Held, for this information on Nancy Boyd Willey’s important contribution to Sag Harbor, and to Steve Sikora, The Willey House Museum, for his help and kind permission to use historical photos.

Nancy Willey*

Barcelona Neck

Willey in 1934 #

Willey House Museum #

The Long Pond Greenbelt +

The Lady Caroline Maureen Hamilton Temple Blackwood

Lady Caroline Blackwood (1931-1996), Guiness heiress, novelist, biographer, journalist & critic, had an unhappy, abusive-nanny childhood. She described herself as "scantily educated" and was a plump, awkward teenager who blossomed into a lithe blonde woman with startlingly big blue eyes. She began her writing career as a journalist, and was noted (and criticized) for writing negatively, immediately showing an acerbic wit and tongue.

She eloped to Paris with Lucian Freud, and had, amongst many others, an affair with Robert Silvers, founder of The New York Review of Books, married composer Israel Citkowitz and later poet Robert Lowell. She was even with photographer Walker Evans for a time.

Lowell encouraged her to write her first book, For All That I Found There (1973), a memoir of her daughter’s treatment in a burn unit. Blackwood’s novel The Stepdaughter (1976) is an taut monologue by a rich, self-pitying woman deserted by her husband in a plush New York apartment, tormented by her fat stepdaughter, which won the David Higham Prize. Great Granny Webster, about her miserable childhood, was short-listed for the Booker Prize.

Other books are The Last of the Duchess, about the Duchess of Windsor, and The Fate of Mary Rose (1981) which describes the effect on a Kent village of the rape and torture of a ten-year-old girl named Maureen, narrated by a selfish historian whose obsessions destroy his domestic life.

A famous painting of her, pictured, by Lucian Freud titled “Girl in Bed” figured in the death of Robert Lowell. Their marriage was a wreck when he left Ireland and flew to New York City, arriving at the apartment building where writer Elizabeth Hardwick, whom he’d left for Caroline, also lived. Hardwick was summoned by the taxi driver, who found Lowell slumped over in the back of his cab. When the door was opened she found Lowell, dead, clutching “Girl in Bed”.

After having lived with Lowell in England, Blackwood moved to Ireland to avoid taxes, and in 1987 settled in the house at 8 Union Street, Sag Harbor, continuing to write until her death from cancer in 1996.

Blackwood by Lucien Freud

8 Union St

"Dangerous Muse"

"The Last of the Duchess"

Betty Friedan, the Woman Who Changed History

Betty Friedan (1921-2006) published a book in 1963 that galvanized American Feminism in the second half of the 20th Century. Earlier feminists like Cady Stanton and Victoria Woodhull could probably not have imagined the shock effect The Feminine Mystique had on the general public, and by the year 2000 more than three million copies had been sold, and it had been translated into many languages. The Second Sex, an earlier book by French author Simone de Beauvoir, also dealt with similar issues but did not quite strike the same cultural nerve. The Feminine Mystique exploded the pervasive myth that a woman kept by her husband in a housewifely role is necessarily a fulfilled woman: “The problem that has no name”, as she called it.

For Friedan its publication also let to her co-founding and being the first president of the National Organization for Women in 1966, which sought equal rights as well as standing with men in American society. This was followed by the Women’s Strike for Equality in 1970, which took place on August 26th, the 50th anniversary of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, giving women the right to vote. It is now hard to believe that less than 100 years ago women needed to be “granted” the right to vote, and Friedan was an important part of this huge change in culture. She also worked hard for the Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution, and in spite of her influence and hard work, it was never passed. She was slow to accept the cause of homosexual rights, but eventually saw its essential worth.

Friedan was brought up in a liberal Jewishhousehold in Peoria, IL, graduated from Smith College summa cum laude with a major in psychology, and became a journalist, but was ironically and significantly dismissed from the union newspaper UE (United Electrical) News for being pregnant, after which she freelanced. She was temperamental, egotistic, and abrasive, and raised three children with her husband Carl. Her marriage ended in divorce in 1969. Friedan summered in Sag Harbor, spending more and more of her time here later in life at 31 Glover Street. Local historian Anthony Garro, who has guided many walking tours in Sag Harbor, was standing outside her house once with a group. A neighbor suddenly shouted from down the street, “That woman ruined my life!!”, because she had read The Feminine Mystique in the hospital after giving birth, and subsequently left her husband.

There is no question that Friedan’s book and work has had enormous effect on culture worldwide, and its importance is undiminished.

Betty Friedan

"The Feminine Mystique" by Betty Friedan

Marching for the ERA (photo: Dr. Peter Couri, Betty Friedan Tribute website, Bradley University)

Annselm Morpurgo: “Come Out of the Closet”

The Morpurgo house at #6 Union St. is now condemned, but it was long the home of the Morpurgo sisters, Annselm and Helga, and as Tom Clavin put it in one article on the Morpurgo legacy, it was “Sag Harbor’s own version of Grey Gardens” although the Morpurgo Sisters would prefer to have it known as "Sag Harbor's Vietnam" since it became a battle ground between a proud family and what the sisters perceive to be a local political machine, greedy to appropriate what is not theirs. The outcome of the parcel has still not yet been determined, and Annselm is hoping to raise needed funds for it to be rescued and become a museum.

Annselm (Annaselma) Morpurgo was born in 1934 in Italy. One grandmother was the Baroness Ida Sierra Morpurgo who spent years in Alexandria, Egypt teaching the harem of King Farouk how to read and write English while married to Baron Annselmo Morpurgo, heir to the Egyptian Office of Generali A.G., the family multimillion-dollar corporation which funded the United Kingdom's building of the Suez Canal. Annselm's mother was Lady Adele Vilhelma Ludvikke Larsen-Nilsen, better known as the Scandanavian artist Vilna Jorgen. Her father, Baron Attilio Giacomo Morpurgo, was a physician who prevented a diphtheria epidemic in a fascist youth camp during his military service in the Tyrolean Alps for which he was gratefully appointed by Mussolini Assistente Primario of the United Hospitals of Rome, until Hitler compelled the firing of all Italian Jews.

"After Hitler’s alliance with Benito Mussolini in 1937, Annselm’s mother was commissioned to create a sculpture of the two dictators for a public works project. While working on it (as slowly as possible), Jorgen prepared an escape plan for her family. It would be necessary because the work of art she created depicted both Hitler and Mussolini as beheaded monsters. After it was completed, having milked the commission to the max and stayed on the dictator’s good side, Jorgen took a hammer to the sculpture and destroyed it, prudently declaring it "unworthy of showing". She and her husband and two daughters (Helga was born a year after her sister) managed to get on a boat to the U.S. in June 1940, the last day before the British barricaded Gibraltar. The family landed in New York City.” (Tom Clavin, from the East Hampton Press)

The Morpurgos were hungry, lived in tenements, and suffered the worst privations of poor immigrants, including rat bite fever and pernicious anemia. But after growing up, Annselm, in her family's feminist tradition, coined and stylized the Unisex movement which predated the Rainbow Coalition. By 1953 she and her wife, Billie Ann Taulman published the first newsletter of The League, an early gay rights organization which later became New York Mattachine.

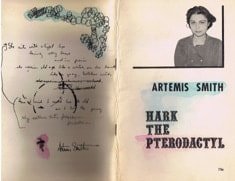

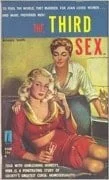

The Human Rights Partnership of Annselm and Taulman published “lesbian pulp fiction” under the name Artemis Smith - sexy gender-bending works that stealthily inserted the Rainbow's message to millions of readers worldwide. Annselm has reissued the original works together with memoirs and commentaries, which are widely read today in print. But it was in 1964, while addressing the East Coast Homophile Organizations Conference in Philadelphia, that she made history forever by urging the gay members of her audience to “come out of the closet or be left out of the civil rights putsch”.

Annselm, a professor of scientific philosophy, is also now published as ArtemisSmith. As the head of the Savant Garde Institute, a futurist 'think tank', she writes: "My lifetime goal is still to achieve the Nobel Prize for making a world-shaking contribution to the history of ideas. The central theme to my life's work in literature and philosophy of mind is that Human Identity is not defined/limited by either anatomy or biology, but is evolutionarily transcendent even as our species reaches out and attains higher forms of information processing/exchange.”

Helga Morpurgo now lives, paints and writes in Arizona, but Annselm is in New York, heading the Savant Garde Institute.

Ed. note: Our thanks to Annselm Morpurgo for reviewing this text for inclusion, and to Tom Clavin for permission to reprint the quote above.

Vilna and Annselm §

"Hark the Pterodactyl "

Morpurgo Family in 1949 §

"The Third Sex" by Artemis Smith

“An Open Door Since 1844”: Christine Grimbol

Christine Bech Rannie Grimbol (1945-2000) was born in Bristol, PA, to a mother who died in childbirth and whose father and three-year-old brother drowned when she was only 10 months old.

Going to live with an aunt, she then suffered years of sexual abuse from her uncle. When her aunt died, she was sent to another relative, finally finding solace and salvation in the church and the choir. She received a degree in music from the Westminster Choir College, and a divinity degree from Princeton Theological Seminary, where she met William Grimbol. While serving at a church in Milwaukee where she ministered to battered women and fought racism in schools, she and Grimbol, also a minister, married. The Grimbols then came to Sag Harbor in the mid-1980s to serve the small, aging congregation at the First Presbyterian (Old Whalers’) Church, a National Historic Landmark.

Like many people who arrive in Sag Harbor, Chris Grimbol thought of it as her first real home and hometown, and set out to befriend the community. She hung out with the tough-talking fishermen at the delis, wrote sermons while chatting with patrons at the Paradise Diner, and very deliberately set out to meet the youth of Sag Harbor. When Chris and Bill were students at Princeton, classmates had nicknamed her “Easter” and him “Black Friday" because of her more upbeat view of her faith, which he claimed eventually rubbed off on him. She was intent on giving the kids of Sag Harbor purpose and hope, and Bill Grimbol remembered her going up to a group of hardened kids shortly after they'd arrived, saying “The youth group meets on Sunday at 6:30pm. Where do you live? I’ll pick you up.” He added, “It was like the Charles Manson boys’

chorus. She just went and got everybody."

No one, regardless of race or sexual orientation, was off her radar, and she was fearless about sharing her own personal story. As Annette Hinkle aptly put it, she saw the church as a hospital for sinners, not a sanctuary for saints.

Esther Ricker, who’d been part of the church governing committee that hired Ms. Grimbol, said that in 1957, when she first joined the church, if there were 25 people there on a given Sunday that was a lot. Before Chris Grimbol’s death, almost 600 people packed the church for Easter Sunday.

Grimbol coined the motto of the church in 1994, at its sesquicentennial, "An open door since 1844". She then added, “And we’re not about to close it now”.

Besides her church and hospice work, Ms. Grimbol helped found the East End AIDS Wellness Project and worked for feminist causes, supporting the pro-choice movement.

Complications from gastric bypass surgery led to her death in April, 2000, at the age of 54. Red roses and black ribbons were strewn on the steps of the church in her honor, and 1,000 mourners were present for her funeral.

Christine Grimbol

First Presbyterian (Old Whalers”) Church‡

Grimbol Playing Guitar ‖

Contemporary Hero Linda Gronlund

Linda Gronlund was born September 13, 1954 and died, significantly, on September 11, 2001. Her mother, Doris, owned the Sagalund Store clothing store until 1997. Linda graduated from Pierson High School in 1972, went to Southampton College, and earned a law degree from American University in 1983.

A lover of nature and an accomplished sailor, scuba diver and brown belt in karate, Linda was also an avid race car enthusiast and at the age of 12 restored a car with her father. She worked as a flagger at the Bridgehampton Race Track and was a member of the Sports Car Club of America.

She eventually landed her dream job, as Manager of Environmental Compliance for BMW North America.

On September 11, 2001, she and her boyfriend Joe DeLuca boarded UA Flight 93 from Newark bound for San Francisco. They were on their way to travel to wine country to celebrate her upcoming 47th birthday.

Linda was in seat 2A, Joe next to her in 2B, sitting right behind one of the highjackers. As the highjacking took place, passengers called families and learned about the other attacks. Linda called her sister beloved Elsa, telling her where her will was, and also told her family how much she loved them.

Doris Gronlund is sure that Linda would have been among the group of passengers who fought back and kept the plane from reaching its target, when it crashed into a field in Shanksvile, PA. As she said in an interview in the Sag Harbor Express, "I always want people to remember Flight 93 because they were unique. They did not choose to let that particular plane become another missile so the next target, the White House or the Capital would be destroyed. What a different picture we would have of that day if that had happened."

BMW has set up a scholarship in her memory, awarded annually to a female engineering student at MIT, and Barcelona Neck Preserve was renamed the Linda Gronlund Memorial Nature Preserve on September 11, 2004.

Ed. note: Special thanks to Annette Hinkle for her research on Linda Gronlund, to Elsa Gronlund for permission to reproduce two of the photographs seen here, and to Doris Gronlund, who has remained an inspiration for those who have suffered loss from the 9-11 attacks.

Linda Gronlund†

Flight 93 Dedication (Photo: Chuck Wagner)

Linda and sister Elsa†